A Closer Look At Rabbit Tracks

I have been trying to study Eastern Cottontail Rabbit (Sylvilagus floridanus) tracks with more intention for the past year. I have also wanted to write about something about some of the things I have been looking for specifically when I come across Rabbit tracks. Lately for me, it has been about the individual toes of the Rabbit tracks and their positions. The toe positions can tell us a lot about which of the feet we may be looking at. Is it a left front or a right front? If we look close, and know what to look for, the toes will tell us. This isn’t always necessary when we see a whole group of Rabbit tracks, with all four limbs clearly laid out in a bound as we often come across them, but instead knowing the individual clues to specific feet, say a left front, can reveal some more details which otherwise would be invisible.

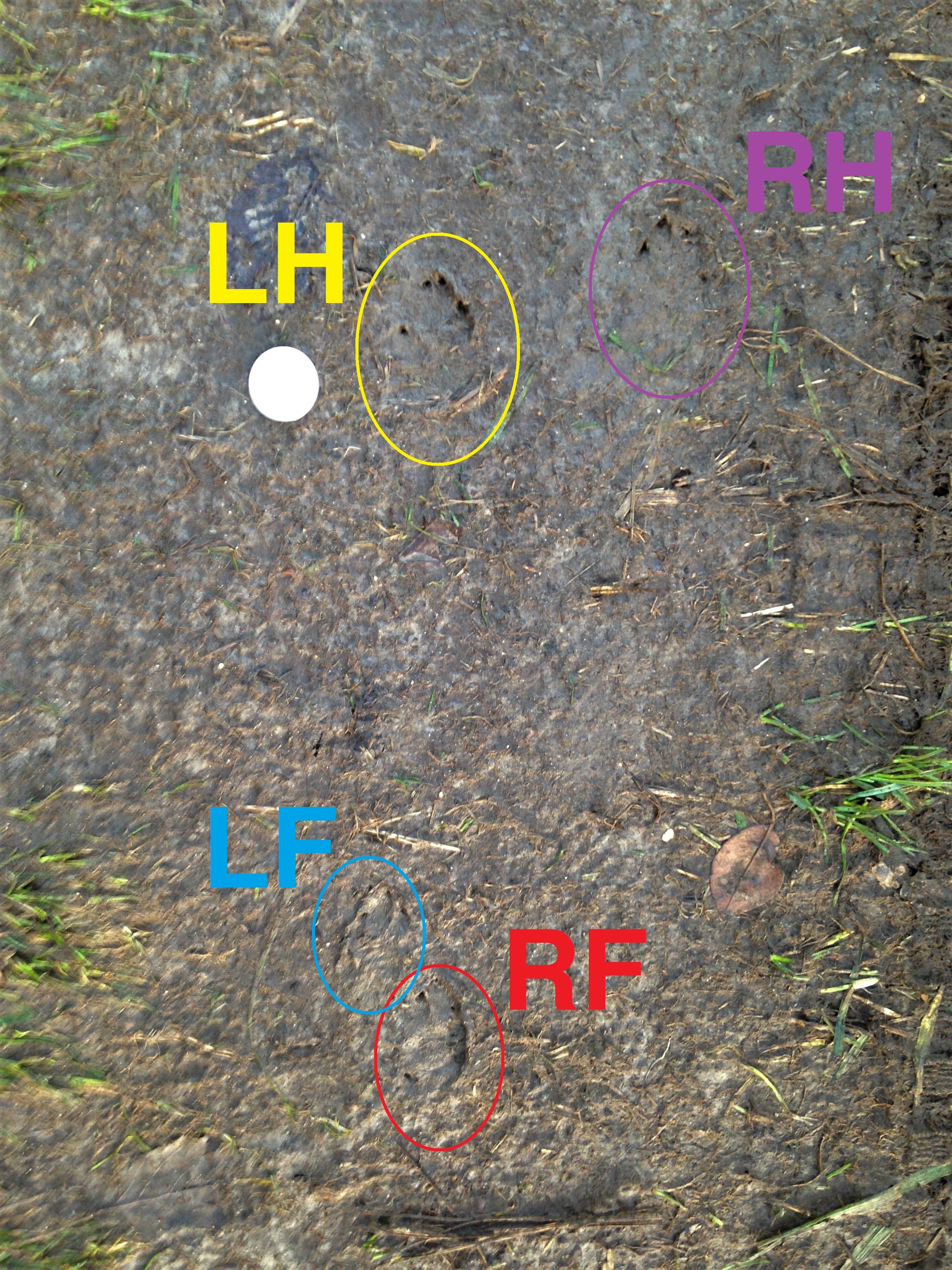

Let’s look at a typical group of Rabbit tracks, in a bounding gait.

The gait in the photos, again, is a bounding gait, meaning that the hind feet (at the top of the image) are landing generally in line with each other beyond the front feet, and then pushing off simultaneously, or just about. Then using the force of the hind feet the Rabbit is airborne for a moment until the fronts touch the ground. Then when the fronts push off the Rabbit swings their hind feet on the outside of and beyond the fronts and again the Rabbit is airborne once more until the hinds touch the ground past where the front feet just were.

The front legs are smaller and relatively shorter while the hind legs are larger and longer and provide the propulsive force for the bounding gait. Because the hind legs have more power than the fronts there is a longer leap when the hinds push off, thus a greater distance between the hinds to the fronts, then say the fronts to the hinds. If need be, this video make make more sense.

I hope I have made sense of the bounding gate. I have included a couple of links at the base of the page so that you can do some follow up research to help understand this and other gaits a little better. These things come with time learning and time observing, or “dirt time” so be patient with yourself and keep at it.

For now, let’s look at the characteristics of Rabbit feet and toes to get on the same page around nomenclature that I’ll be using from here on out.

Rabbits are mammals. They share the same 5 digited common ancestor as all modern tetrapods (four-footed animals). The ancestral forebears likely had 5 toes on both front and back feet. Some mammals lost some of their toes along their evolutionary path, and some even lost some of their feet, like Pinnipeds (Seals), Whales and other Cetaceans. We kept our five digits, but Rabbits lost some. On a Rabbits front feet there are 5 toes but the first toe is greatly reduced. It may be that this toe has been retained through the evolutionary process, but no longer has a function or use (which is known as “vestigial”). On their hind feet there are only 4 toes and no vestigial toes. This is helpful to understand when looking at tracks of Rabbits because sometimes we can see those vestigial toes. Below is a photo of a track created by the left front of an Eastern Cottontail Rabbit.

If you use the arrows on the side of the images you can navigate between the labelled toes and the photo of the unlabelled toes. I have circled and numbered the toes. If you look at the toes you can see that the toes are pretty asymmetrical with some toes extending further from the than others. Toe 1 is a really small, but still has a claw which registers in the mud. Toes 2, 3, 4, and 5 all make a sort of inverted, and backward “J” shape and by looking for this “J” shape we can start to tell right and left front feet on Rabbits and Hares.

Within the inverted backwards “J” shape, I also look for the positions of toe 2 and toe 3. They are close to each other, but toe 3 is generally higher on the horizon of the toes then toe 2 or toe 4. This pointedness was what I first starting seeing when I initially began noticing the Eastern Cottontail Rabbit tracks in the mud. This pointedness in the foot can also be useful to determine the direction of travel when you only have a partial track or are missing the rest of the bound. Keep an eye out for it as you begin looking for Rabbit trails.

Again the front tracks are also smaller than the hind tracks as the front feet are smaller than the hind feet, as mentioned to earlier.

Next I want to take a good look at the structure of the hind feet and the position of the toes, specifically toes 3 and 4. Remember that the hind feet only have four toes, and we start counting from the inside out, and even though toe 1 is no longer there, we still count the same way, starting from the inside of the foot counting up as we move along towards the outside of the foot.

Note how toes 3 and 4 are pretty even along the leading edge of the hind track. This seems to be pretty consistent in what I have seen and I use this as an indicator of a hind foot if the track is only partially visible in the substrate. Sometimes the foot will not register in harder substrate, but the claws usually do.

Lastly, I wanted to offer a couple of images of the skeletal structure of Rabbit feet so that there is a better understand what makes up the structure of the foot.

Drawings from “Deformed claws in a rabbit, after traumatic fractures”, see link at bottom.

The photograph below is a left hind foot, I believe.

The semi-intact left hind (I believe) foot from an Eastern Cottontail extricated from a Great Horned Owl pellet, 2021.03.16