Atlas Bone of White-tailed Deer

On one of my tracking study calls a photo was presented and everyone was asked to identify the bone that was shown. Somehow a few people were able to identify it rather quickly. I had never heard of the bone before but took note. I love learning about the skeletal structures of animals and spend a lot of time on it, but how did I miss a bone that so is so important to an animal, and that so many others knew? Those folks who knew the bone also mentioned that the identification of this bone was a question that had come up on a track and sign evaluation and that means it could come up for me as well. I needed to learn more about this bone.

Flash forward a year and a half. I am wandering through a large urban woods, mostly composed of Eastern White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) growing in lower wet areas. My companion and I were distracted by tracks of White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and ended up a little bit disoriented as to the way back to the cars. Feeling a pressed for time I wasn’t in my best mind for orienteering and was starting to feel anxious about the clock. We turned in the direction of where we thought the path would eventually be and there, about five meters ahead, in the snow and old orange fallen Cedar leaves which littered the ground was a bone. I walked up, now full of an inquisitiveness which beat back the anxiety I picked up the bone and remembered which it was right away. The atlas bone.

My friend asked about the bone and I explained what little I could at the time. I told them that this is the bone which sits directly behind the skull, the top of the spine, and that I believed it to be from a White-tailed Deer. I mentioned that I really I didn’t know anything else, but now that I have seen and held the bone, I would go home and learn more.

Here is what I am learning about the atlas bone.

What I mentioned above is correct. The atlas bone is the first vertebra of the neck, the cervical vertebrae, and it sits directly behind the back of the skull, slipping over or articulating with the occipital condyles. Since it is the first of seven cervical vertebrae it is also known as C1.

At the back of the White-tailed Deer skull there is a large opening or hole named “foramen magnum” which literally translates to English from the Latin as ‘big hole’. This big hole meets up with the hole which goes through the center of the atlas bone to allow the spinal cord to pass through from the neck to the brain.

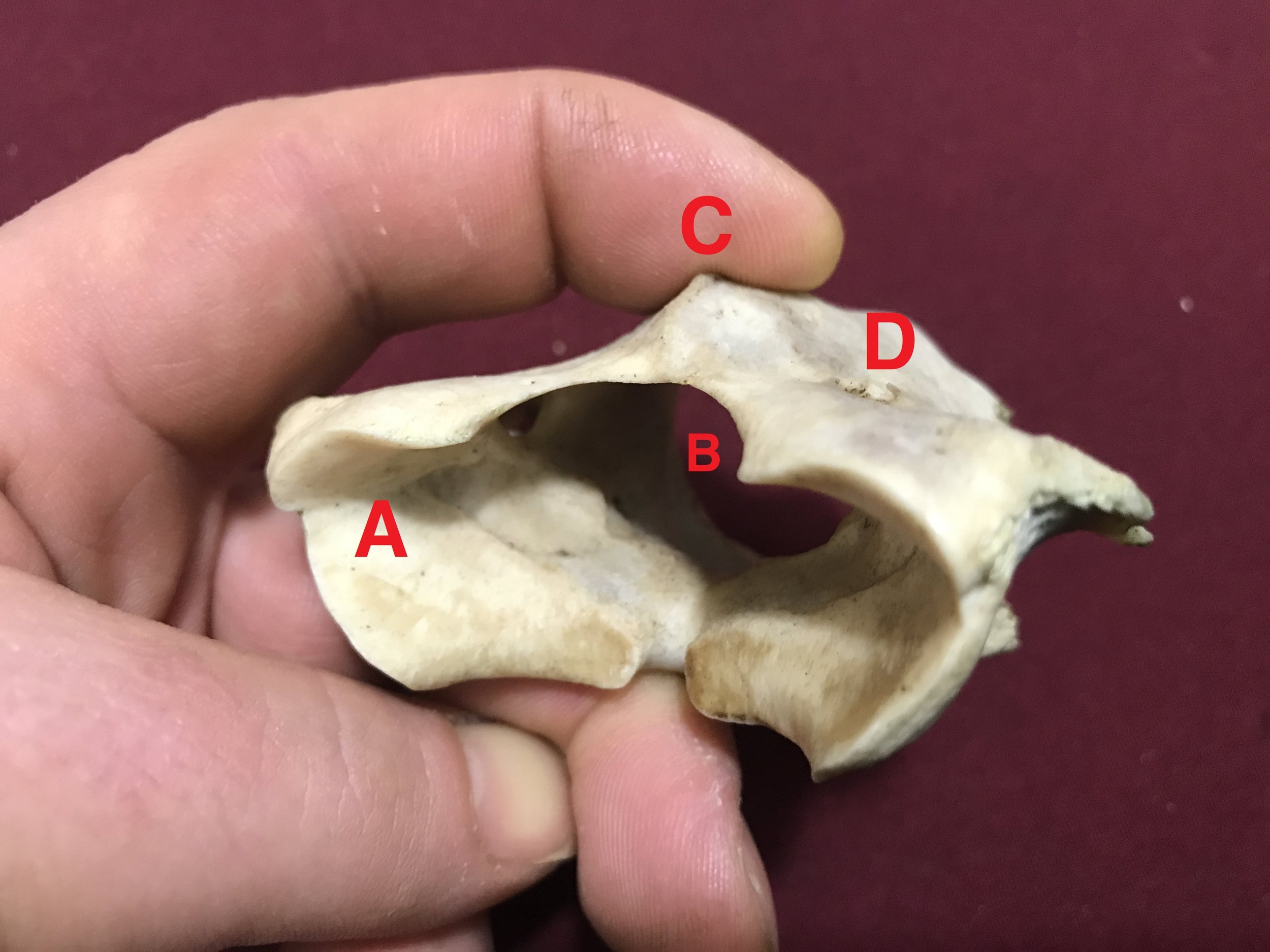

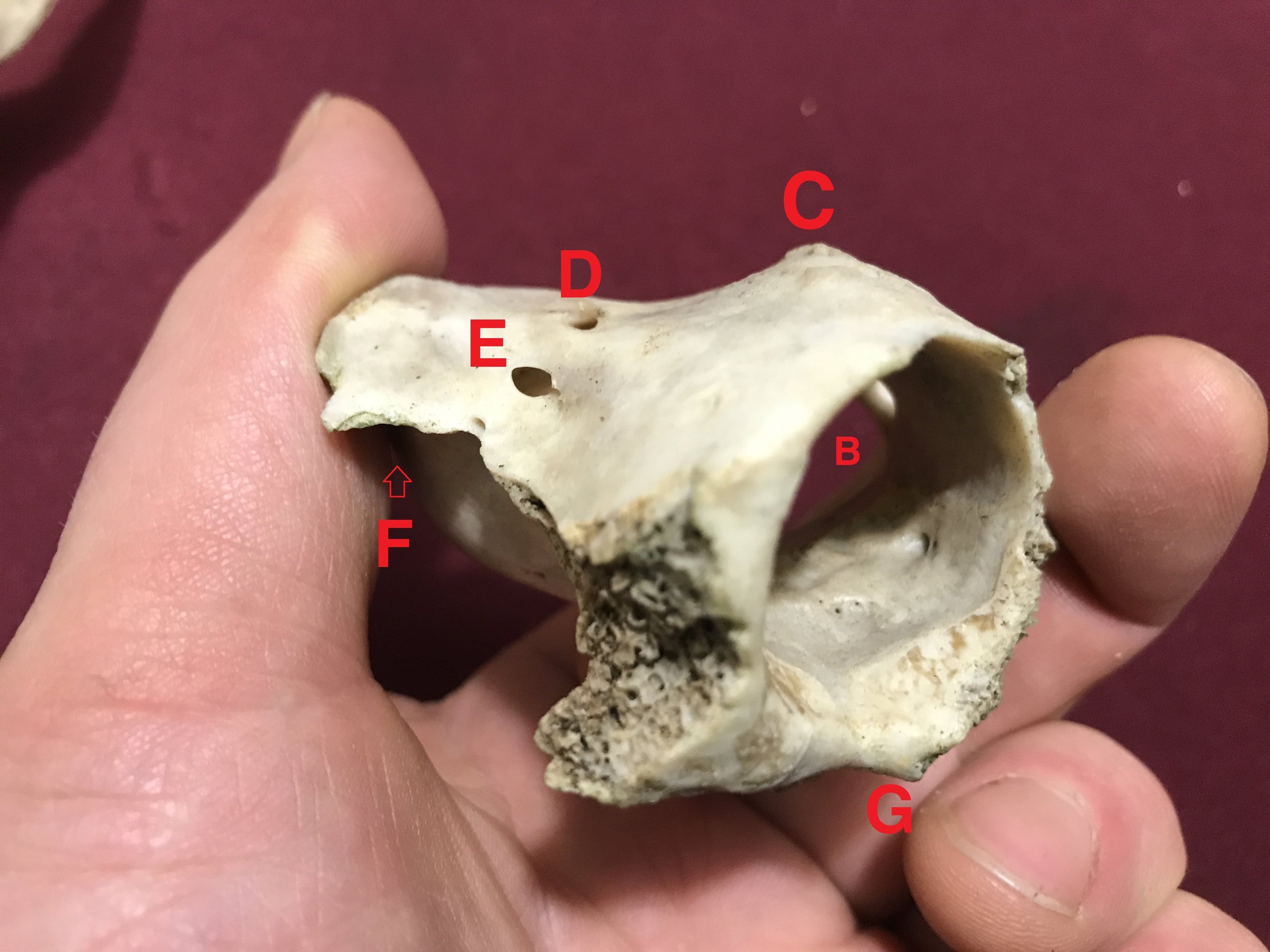

Like the skull, the atlas bone has many facets and foramen of it’s own.

A : Cranial articular surface - where the bone cups the paired occipital condyle bones of the White-tails skull.

B : Vertebral foramen - where the nerve conduit known as the spinal cord sits protected within the sheath of the spinal column.

C : Dorsal tubercle - where muscles attach to the bone.

D : Alar foramen - for vertebral arteries to pass through.

E : Transverse foramen - for more passage of vertebral arteries.

F : Atlantal fossa - the depression or hollow “armpit” below the shelf-like atlantic processes ( or “wings of atlas”).

G : Ventral tubercle - provides attachment for supportive ligaments.

The skull would be to the front (anterior) of the atlas, the axis is to the rear (posterior), followed then by five more cervical vertebrae of the neck, Most mammals have 7 cervical vertebrae (C1 to C7), but some Sloths have six, and Anteaters have nine.

The shape of the atlas and axis cervical vertebrae a pretty different from the five other other cervical vertebrae. The joint between the skull and the atlas bone allows for the most movement between any of the vertebrae in the entire spine. This is to provide a lot more range of motion in the neck and freer movement of the head, all while still protecting the spinal cord. I tried measuring the vertebral foramen (B in the images above) and the hole was 25 mm in diameter. I would love to get the chance to measure atlas bones from White-tails whose age is known or figured out from looking at their teeth.

With many bones there are cultural narratives imbued in our understanding of them. Tools, practices, and cultural readings of bones which shape how we look at the bones, but also how our understanding of the bones shape us and the worlds we create. Think of the cultural significance of a skull, or the biblical patriarchal implications of Adam’s rib. I feel like the atlas bone carries the same weight.

In case you didn’t know, according to old Greek myth, after a war between the Gods and the titans, Zeus punished the great titan Atlas to carry the celestial sphere (the sky, the stars, the heavens, etc) on his back forever. Only once did Atlas get relief, for a moment when Hercules who was on a mission for a king took over for carrying the heavens. To help Hercules, Atlas went to go get some golden apples from a tree which was protected by the Hesperides. While he did this, Hercules took over carrying the sky and Atlas went and got the apples. But when Atlas returned, instead of immediately taking back the heavens, he told Hercules he would bring the apples to the king himself. Hercules realized he was going to be stuck carrying the firmament so he in turn asked Atlas if he could hold the sky just for a second while he got a lion skin cloak to use as a bolster to help him carry the weight of the heavens. Atlas agreed and took back the weight. As soon as he did this, Hercules made it known that he was no longer going to take the heavens and Atlas was stuck with the task once again.

I want to refer to a paper published in 2021 in Journal of Anatomy by David J. Jackowe and Michael G. Biener, titled Atlas and Talus, where the authors discuss the shifting nomenclature of the first and seventh cervical vertebrae and a bone in the foot. They write that C1, the bone which we call the atlas bone wasn’t always named the atlas bone. Instead C7 was called the atlas bone.

Think of those paintings and sculptures of the titan Atlas carrying the sky on his shoulders. He isn’t supporting that weight at the back of his skull, but instead the last cervical vertebra before the thoracic vertebrae begin. This is a region on my back where I carry heavy things too. The authors note that sometime in the 1700’s anatomists began naming C1 the atlas bone instead. This implies a shifting of where humans carry their burdens, from the back of the shoulders up to the back of the skull. The logical brain becomes the new world to carry, and becomes the new way to engage with being, a new way to engage with the world around us.

I read this and I start to see a displacement of how we encounter the world. Instead of through the sensuous engagement of muscle and the physical body, our engagement shifts to the cerebral, to the brain and analytical. We are leaving the burdens of the world, the impulses and desires behind and instead becoming more computational, rational, logical and less physical and sensuous. I feel like this isn’t just in the world of anatomy, but instead echoed across multiple western sciences and ways of looking at the world. The renaissance is full of it. I wonder at how we can restory and restore these implications, encouraging a more sensuous and engaged reading and understanding of how we can be in, and how we carry our understandings of the world?

This is all just something to think about the next time I am managing a heavy load. I also sort of wonder what the White-tailed Deer think of this? Do they need more skeletal support at the base of their heads considering the males antlers? Or at the base of their necks where they carry the neck, the head and the antlers? Where do they carry their weight? Where do I carry most of mine?

To Learn More :

Osteology of the White-Tailed Deer (with link to download the pdf)

Skulls and Bones : A guide to the skeletal structures and behavior of North American mammals by Glenn Searfoss. Stackpole Books, 1995.

The cervical (neck) vertebrae and how they move by Rod Nikkel

Atlas and Talus by David J. Jackowe, Michael G. Biener