Carrion Beetles pt. 2 : Elytra in the Pellet

“A yellow-and-black burying beetle, crawling across the white fur of his belly, stopped, waved its short, curved antennae and then moved on again… these beetles come to dead bodies, on which they feed and lay their eggs They will dig away the earth from under the bodies of small creatures, such as shrew-mice and fallen fledglings, and then lay their eggs on them before covering them with soil.”

- Watership Down, Richard Adams.

While out with the Earth Tracks Wildlife Tracking Apprenticeship crew, Saturday was spent focusing on Pressure Releases in the sandpit. You can read about this from a previous year here. It is always pretty awesome, studying the links between small peaks, ridges, crests and caves in the sand and how they reflect the sometimes forgettable movements of someone who just walked through the sandbox a moment before. But as much as I love working in the sandbox, I still do get a lot more excitement just being out on the land looking at the signs that those who we share this space with leave behind. Just as the small look over the shoulder is revealed through a deeper impression on the left side of a foot, the small puzzles we discover on the landscape, once studied and deciphered can reveal profound relationships between multiple varied and diverse cohabitating species.

Only an hour into our meander through Allen Park Conservation Area we came across some small fawn trail which we were backtracking up a steep hill. When we got to the top a couple of us were looking intently at the ground trying to stay on the fawn trail. I remember staring at the grass really hard, as though I could stare hard enough the grass itself would burn away and only the sandy trail would remain. I saw grasses, pine needles, White Campion (Silene latifolia), owl pellets, Ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) sprouts, …. wait a second. I went back to the owl pellets. There were many of them, all fairly flattened, and kind of strewn about, as if they had been rained on many times and perhaps walked on by many hikers unaware they were underfoot. Luckily the pillowy duff of pine needles, with sand below, along with the mixed grey hairs of the pellet were cushion enough to cradle many of the bones so that they did not break under compaction.

I sat down immediately and took off my pack. I began first pulling out the bones, which included a couple of hips, skulls from a Short-tailed Shrew (Blarina brevicauda) and a Star-nosed Mole (Condylura cristata), some fine small greasy hairs likely from both. I wish I had taken more time with the larger Star-nosed Mole skull as I haven’t really inspected one thoroughly before, but I got distracted by a different discovery amidst the pellets; elytra. Elytra, or elytron in the singular, are the hard wing covers of a Beetle. If you can imagine a Ladybug, their red and black speckled “shell” which splits apart to reveal the wings are the elytra. Insects generally have two sets of two wings, but for Beetles, the anterior wings (aka the forewings), the ones closest to the head, are hardened and serve to protect the abdomen and the hind wings which are concealed beneath the elytra. The Order which Beetles belong to is called Coleoptera, which translates to something like “sheathed wings”.

The two elytron I found within the smushed pellets had a familiar pattern to an insect I am coming to know. I am generally pretty interested in insects and invertebrates of all sorts, but recently I have been severely focused on a specific subfamily of Coleoptera, or Beetle family, and that is the Nicrophorini. This includes the species Nicrophorus tomentosus which I wrote about here. I am interested in this subfamily because of their habit of hanging out on dead stuff. If you know me, you know I love dead stuff. I love skulls and kill sites and food (which is really just dead stuff consumed), and so it tracks that I would also come to love these Carrion Beetles, as they are commonly known. Members of the Nicrophorinae subfamily are also known as Burying Beetles as they have a habit of burying the carcass’ they encounter. Another common name for this crew are the Sexton Beetles - a sexton is a person hired by a church to take care of the buildings and structures of the church along with the commonly neighbouring graveyard.

Basics of the Nicrophorinae subfamily (and only member tribe Nicrophorini):

They are comparatively large Beetles, which is likely why I take so much notice. They have 10 segmented clubbed antennae, and have dark coloured elytra with red-orange markings on them (which remind me of both the Batman symbol and Charlie Brown’s sweater).

In southeastern Ontario, there are seven species of Burying Beetle (subfamily: Nicrophorinae, genus: Nicrophorus). These species include

Nicrophorus orbicollis : primarily been found in forest habitats; however, they have also been captured in open fields, forest edges, and wetlands.

N. sayi : found in forest habitats, especially in coniferous forest, but they have also been captured in open fields at lower abundances.

N. tomentosus : found to be abundant in all habitat types. That previous article mentioned above is about this species.

N. pustulatus : enigmatic species, captured only very rarely in forest habitats and occasionally open fields. Maybe specialists in forest canopies?

N. hebes (previously N. vespilloides) : found almost exclusively in wetland habitats such as Sphagnum bogs and cattail marshes, occasionally occurring in other wetland-bordering habitats.

N. marginatus : only occurring in large open fields and meadows

N. defodiens : found only in forest habitats, with some evidence indicating that they may prefer dry coniferous forest.

Now that I know that there are multiple species, I will be, and have been since learning, on the lookout for more individuals in hopes of identifying them. Here is some of what I am learning about the subfamily as a whole.

The name Nicrophorinae may be derived from the word “necrophagous”, which means translates to something like Death Eaters, or Eaters of the Dead, which is pretty metal.

Nicrophorinae species exhibit care by both parents, which is seemingly rare for insects. Nicrophorinae bury the carcass to conceal and protect it from larger vertebrate scavengers who may take the carcass. Invertebrate competitors may attempt to occupy or lay eggs on the carcass, all the more reason to cover it up. All burying beetle species require these small vertebrate carcasses for reproduction, which they often use as a food source and nest for developing larvae and will not remain on a carcass overly infested with flies or larvae from flies (though they can dispatch a couple of maggots here and there).

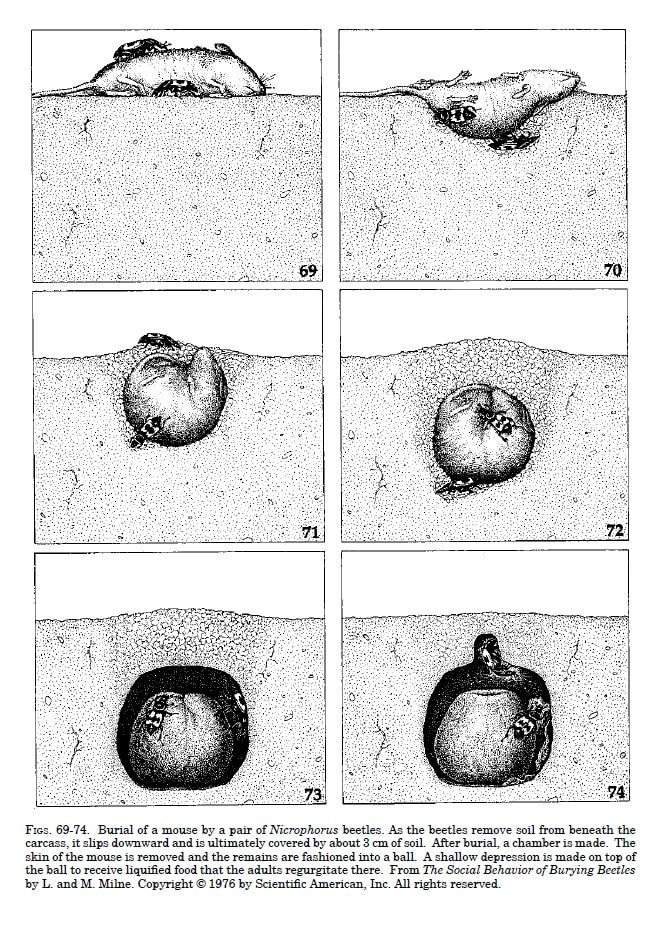

What do they do with a carcass they come across? It’s pretty cool. Two Nicrophorinae Beetles will hang out on a rotting carcass, then mate atop the dead animal, and then crawl under the carcass to begin the excavation of dirt from below as part of the burying process. Once entirely or partly buried, they will remove fur or feathers from carcass and cover the carrion with excretion of a preservative fluid (eww and cool). This preservative fluid helps defend against microbes by slowing down decomposition. They then lay eggs close to the carcass which is utilized by the larva during development.

The two parent Beetles feed early stage larva predigested materials from the carcass. The larva communicate the need for food by touching their legs to the mouth of the mother. Mothers who may be overwhelmed or bothered will actively not feed, or eat their own young who beg too much for food, culling the brood to achieve numbers which can be sustained. No need for birth control when you can just eat your babies. Beetles are metal.

Silphidae Beetles (the family which the subfamily Nicrophorinae is a part of) can produce sound by rubbing the tips of their wing covers against their abdomens. These sounds are called “stridulations”. Three types of stridulations have been recorded; defensive stridulations to ward of predators, mating ritual stridulations to woe their mates while hanging out atop the slowly rotting corpse/dinner/nest for their young, and also parental stridulations to call their young to feed.

It also seems like it is pretty common for small mites to hitch a ride on the Beetles backs. They ride along with the Beetles and then predate fly eggs and larvae. This relationship could be typified as a symbiotic relationship but sometimes the mites may also feed on young instars of the Beetles and if the Beetles are overwhelmed with too mites it may inhibit the Beetles abilities to fly.

This is a really basic intro to this subfamily. I think as I encounter more dead things and thereby more Nicrophorinae Beetles, I’ll get more chances to observe them and to pay closer attention.

To learn more :

Habitat use of co-occurring burying beetles (genus Nicrophorus) in southeastern Ontario, Canada

The Carrion Beetles of Nebraska by Brett C. Racliffe

Introduction to UK Carrion Beetles

BugDay Workshop on Coleoptera Order (Beetles)