Metacarpal or Metatarsal?

I have been thinking a lot about bones lately.. I guess I think a lot about bones all the time, but lately I have been trying to consider them more completely, in relation to one another, and to better be able to identify which bones are which, where they come from on the body, and which bodies the particular bones I find make up? There are so many questions that come wrapped in bone that it’s kind of fun to take the time to consider some of them.

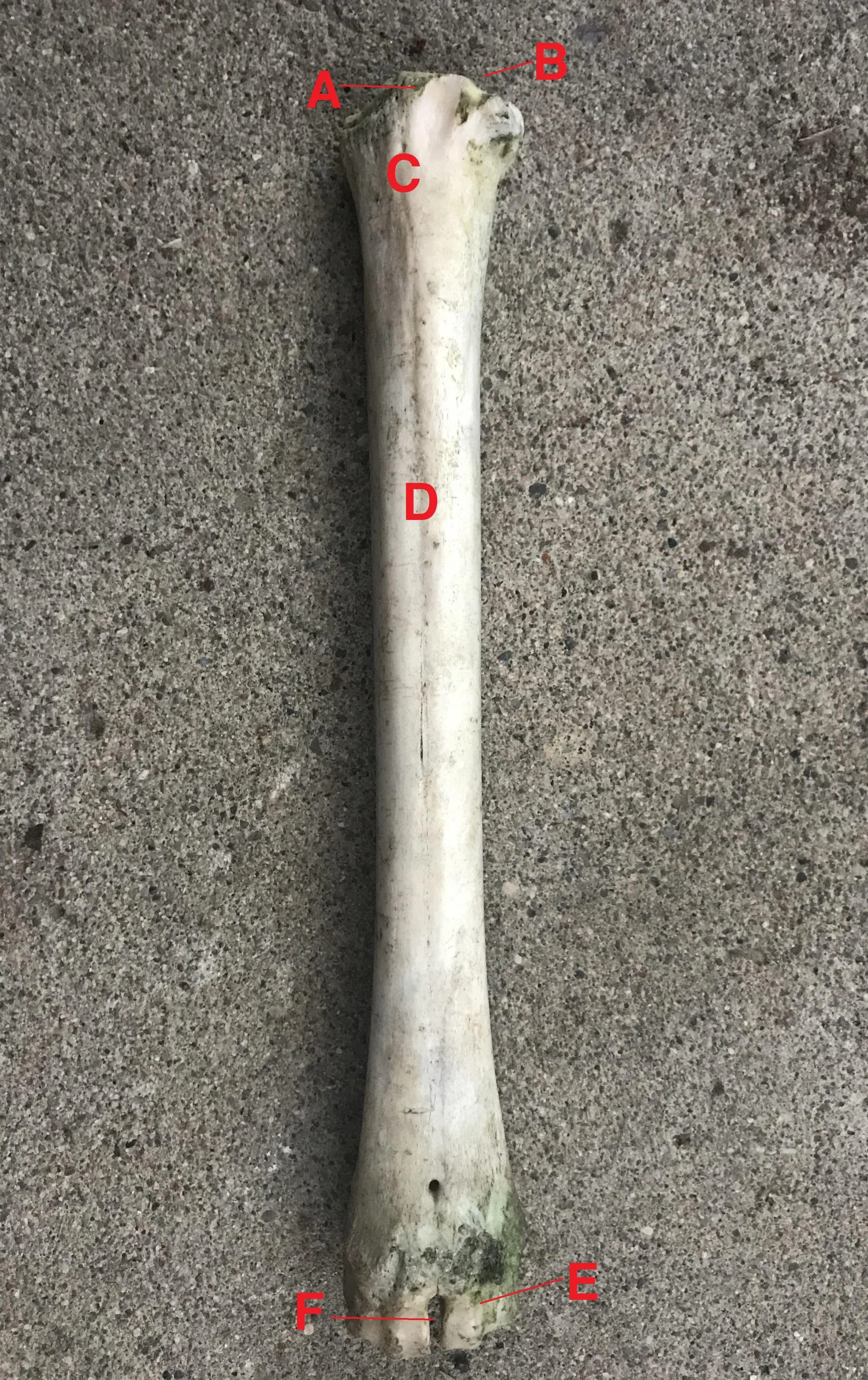

Over the past couple of years I have found a lot of bones I would singularly identify as a leg bone. I could probably name if the bone came from a White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) or not, but beyond that, I was usually stumped. About a week ago I found another bone while out with my students and I wanted to properly identify it. Here’s a couple of photos.

This is a long straight bone which is pretty thick and felt dense and heavy. My assumption when holding it in my hand, feeling the heft but seeing the slimness got me thinking of a leg bone right away. And who around these parts has a leg bone that long, could be found in the Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) woods where we walked that day? It must be White-tailed Deer. About 60 years ago, there may have been Cattle (Bos taurus) roaming though those woods, but this bone was much too slender. Deer must be the answer. But wait a second.. Ungulates, like deer, elk and Cattle have different leg structures than us. It would be smart to look into that a little first.

The metapodial bones - metacarpals and metatarsals - are not leg bones in the way we might think, but rather they are bones of the hands and feet extending from the phalanges of the digits (fingers and toes) up to the carpal bones (wrists). The early common mammal ancestor of both deer and humans had five metacarpal bones in the hand. For us we number our five metacarpals medial to lateral, with the thumb being metacarpal I, through to our little finger being metacarpal V. Deer only have one metacarpal bone, but that one bone is actually two bones which have fused together. How many metacarpals an animal has in their hands and how much space there is between the bones can correlate to how the hands are used (handling and manipulating objects, locomotion, etc). A human (Home sapiens) hand has a lot of space between the metacarpal bones relative to a Striped Skunk (Mephitis mephitis). This implies that a human hand has more capacity for manipulating objects and materials, while a skunk hand may be stronger for digging. If you compared human hands to human feet you will notice that the metacarpal bones in the hand have more distance between them then the metatarsal bones of the feet. This is because the hands have evolved for better manipulation and the feet have evolved more to support the body in an upright position. A deer metacarpal are lengthened and strengthened lending to greater agility moving through a forested landscape as well as greater capacity for speed (this characteristic is also present in Horse (Equus caballus) metacarpals).

Ok, metacarpals and metatarsals are bones in the hands and feet, but which are which? Metacarpal bones are the bones of the front feet analogous to our hands. The metatarsal bones are the bones in the hind feet, analogous to our feet. Carpal comes from the Greek word karpos meaning wrist and tarsal,, also Greek, means ankle. No real surprise there.

Now that I had the species, and a clue as to where on the body, we come to the question of which leg it was? Front or hind? Left or right? With all of these possibilities, I knew I had to do better than just “leg bone”. Is there a way to tell the leg bones apart? Turns out there are some ways too look at the bones which may help give a little insight.

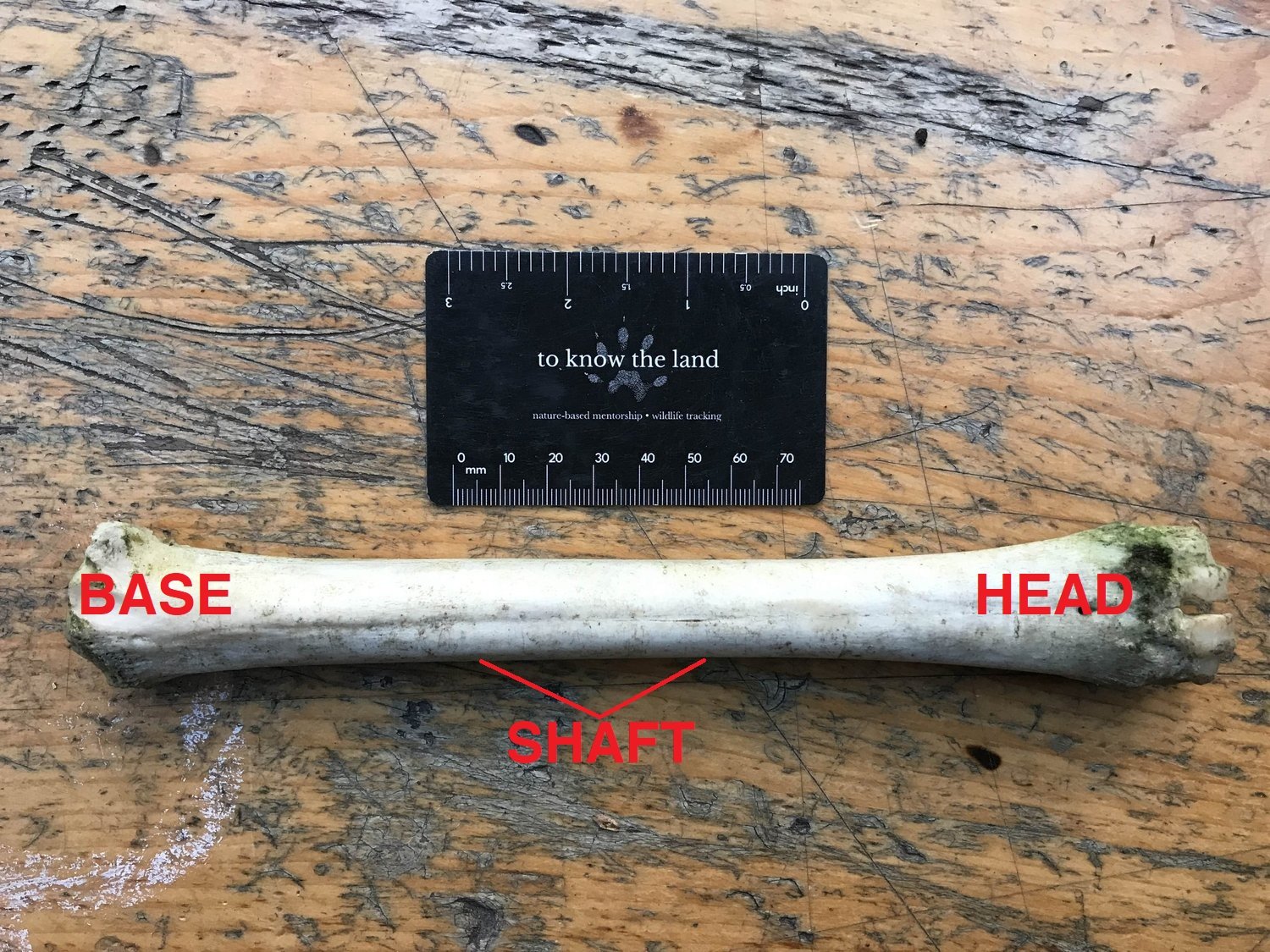

First is length. The bone pictured above is approximately 24 cm (9.45 in) long. A metacarpal for White-tails will measure between 13.6 - 24.5 cm (5.35 - 9.65 in) and the metatarsal comes in at 16 - 28.6 cm (6.3 - 11.26 in). The bone pictured above would be a match for both. What else can we look for to tell the fronts and hinds apart?

When you take a look at the end of the bone pictured above you can see one end with a small hole in it and beyond the hole there are rounded protruding ends of the bone which kind of look like they might plug into or interlock with another bone. This is the distal end, the end which is furthest away from the main trunk or body of the deer. The other end of the bone looks bumpier from the angle of the photo, but if you turned it to look at the end surface, it would be much flatter. This is the proximal end of the bone, the part of the bone that is closest to the body of the animal. When we look at the proximal end of the bone we can tell the difference between a metacarpal bone and a metatarsal bone based on the shape.

The metacarpal bone is shaped more like a D, with a flatter posterior or backside with a rounded anterior or frontside. The metatarsal bone however is shaped more closer to an O than a D. Let’s look at the same view on the bone I found.

Through comparison was able to tell which bone was which with the differentiation discussed above. Noting the D shape of the proximal end of the bone, this is a metacarpal bone and not a metatarsal. So it is from a front foot. But which front foot? You have probably noticed that the left side of the bone is wider than the right side in the image above. In the case of a metacarpal, the wider side of the bone faces the midline of the body, and the narrower side faces laterally, away from the middle of the body. The proximal articular surface (the part of the bone showing in the photo above) of a metacarpal bone of a deer articulates with two carpal (wrist) bones. One of the bones is actually two fused together (called 2 and 3) and the other bone is a smaller carpal bone (called “4” unsurprisingly). The 2+3 fused carpal bone is the larger of the carpel bones and is more medial (towards the midline of the animal) of the two bones. To accommodate the larger size the larger articulation surface (flat area shown above) is the more medial and the lateral side (away from the midline of the animal) is the narrower side. That means this is the right front foot bone of a White-tailed Deer.

Sometimes the little names used in the bones are silly and not important, but since I am trying to learn as much as I can about the metacarpal bone with this post, I might as well learn the names of everything on the bone, too. Here they are, in three different views:

From the back of the deer (posterior):

A. Base

B. Dorsal surface

C. Medial border

D. Lateral border

E. Dorsal longitudial groove

F. Distal vascular canal

Looking head on from the front of the deer (anterior):

A. Base

B. Articular Surface

C. Proximal vascular canal

D. Palmar surface

E. Head

F. Intertrochlear notch

I wanted to use a photo of a White-tail foot to get a little better at understanding where the bone fits in all of this. The deer foot in the photo is oriented the same way as the bone is displayed. The only difference being that the bone would be presented laterally in profile, medial side against the bench, as opposed to with it’s back side or posterior/caudal side down as is shown in the photo. But the head (at the distal end) is close to the hooves, and base (the proximal end) is the end where the hunter had cut this leg from the doe.

Today, before I finished this post I went out to a nearby wood and looked for more bones and found another likely metacarpal, though very chewed up and aged. It’s when I take the time to write up these small investigations, to look at diagrams and create them myself, to share what I am learning in preparation for teaching my students about it, so much more information sticks in my mind and heart. When I saw the new bone today I recognized it like I would a new friend with whom I just had a wonderful long conversation with, learning about their life history and what they aspire towards now. It’s really special to look deeper sometimes.

To Learn More :

Bone Identification.com entry on White-tailed Deer Metatarsal bones

Human and Non-human Bone Identification by Diane L. France. CRC Press, 2009.

The Deer of North America by Leonard Lee Rue. The Lyons Press, 1997.

Anatomy & Physiology by Kevin Patton and Gary Thibodeau. Mosby Elsevier, 2013.

Osteology of the White-Tailed Deer (with link to download the pdf)