Towards A Better Understanding of Scat

Scat : Greek skat-, stem of skōr (genitive skatos) "excrement," from PIE *sker- "excrement, dung" (source also of Latin stercus "dung"), on the notion of "to cut off;" see shear (v.), and compare shit (v.).

- from Online Etymology Dictionary

Ok, so the title might be a bit provocative, but it is the best I have come up with the truly explain what I am getting at. Recently, while the tracking apprenticeship was staying at the Wildlife Research Station in Algonquin Park, we encountered some scat from a few different mammals. The questions kept coming as to the contents, the diets, and the bodies which formed and shaped the scat. I want to explore some mammalian scat a little bit more with this blog post and try and understand what clues the poop might hold to the different physiologies of a few of the species whose scat we encountered.

What is scat? Well, let’s look to the somewhat well known “Scat Rap” written by Andy Bennett, Mary Keebler, and, Rodd Pemble. Doug Elliot added several verses to it and rearranged it with help from Billy Jonas.

It starts with an S and it ends with a T

It comes out of you

and it comes out of me

I know what you’re thinking

You can call it that

But let’s be scientific, and call it SCAT

Scat is yet another word for poo, poop, shit, dung, excrement, crap, feces, turd, droppings, etc. The term seems to only be applied to the excreted indigestible solid materials specifically from mammals. Scat can be made up of all sorts of things. I have found digested meat, hair, teeth and bone fragments, fruit, seeds, grains, grass, plastic fragments, wood fragments, and likely more which was unrecognizable or I just forgot about. Also, scat may breakdown sooner or later depending on the contents. Hair, bone, and other tough durable materials will retain their form and last longer on the landscape than say scat made up of digested meat, soft internal organs, or even some well digested fruit. Scat is helpful in identifying who may be in the area, both by looking at who left it, but also, whose remains may be contained within. While scat can be used to assist in identification of species, it can also be incredibly variable in size, content, shape depending on diet, season, and age of the animal who left it.

Scat is often used by different mammals as a tool for territorial marking. They are often deposited in the middle or at crossroads of trails, on elevated surfaces like rocks and logs. They can indicate through incredibly simple means the shifting territories of the individuals who are present in a given area; no need for borders, fences or walls.

It is important to remember that scat can contain some nasty pathogens such as Hantavirus, Salmonellosis, Giardia, Baylisascaris, and more which can be harmful to humans. When you are investigating scat break it up with sticks instead of your hands, or if using your hands, wear gloves and thoroughly wash with soap and water afterwards. Hand sanitizer doesn’t get rid of all of the tiny fragments the same way as washing your hands can.

And now for the scat.

Algonquin/Eastern Wolf (Canis lycaon)

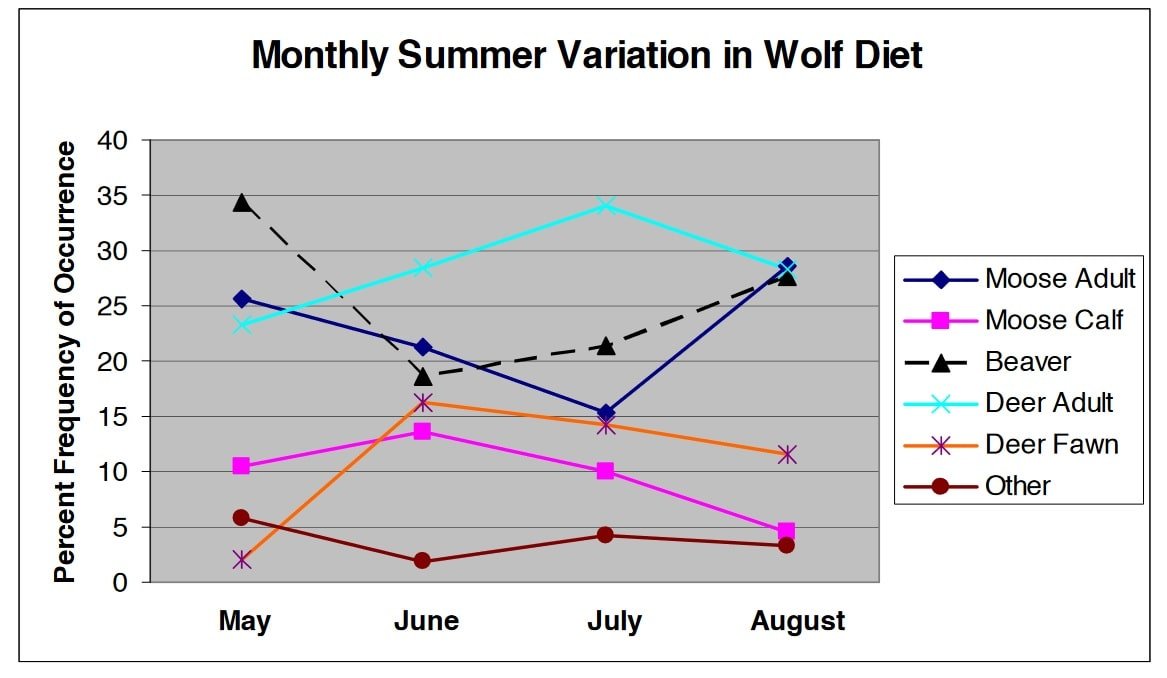

Diet : Meat, fruit. According to Theberge & Theberge (2004), the most common source of food for Algonquin Wolves in Summer months is Beaver (Castor canadensis) coming in at 28.4%, adult White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginanus) 28.1%, White-tailed Deer fawn 9.5%, adult Moose (Alces americanus) 20.4%, Moose calf 9.4%, with other sources making up the final 4.2%. They also note that most consumption of ungulates were adults, with Deer fawns comprising 25% of Deer consumed and Moose calves comprising 32% of Moose consumed.

Dental formula : I 3/3, C1/1, PM 4/4, M 3/2 = 42

Digestion : Carnivore digestion begins in the mouth with their 42 teeth. Their canines are great for puncturing, capturing, holding and killing. Their cheek teeth, or premolars and molars, are good for shearing, cutting and crushing. As material goes in, it is digested with the Wolves highly acidic stomach acids for a longer time than humans, with numbers coming in at 4-12 hrs in my research. Their stomachs then start releasing material into the intestines as energy is needed and then passes in the sequential order in which it was consumed. Length of a Wolf’s intestinal tract is about 3 - 4.3 m, where as a humans intestinal tract is about 7.9 m. Food passes through their digestive system much faster than ours.

Scat : Usually tubular with blunt or tapered ends. Meat scat more amorphous and loose (see frozen scat above). Scat with bone fragments accompanied by hair which protects intestines from puncture. Average diameter of scat from Eastern Wolves found in Algonquin Park is 26.9 mm (Theberge & Theberge, 2004). Scats may be posted on elevated surfaces or trails, roads, and railroads.

Moose (Alces americanus)

Diet : large amounts of vegetation; forbs and leaves in Spring and Summer, while in Winter the Moose diet consists of woody browse, coniferous needles and soft bark from shrubs and trees.

Dental formula : I 0/3, C 0/1, P 3/3, M 3/3 = 32

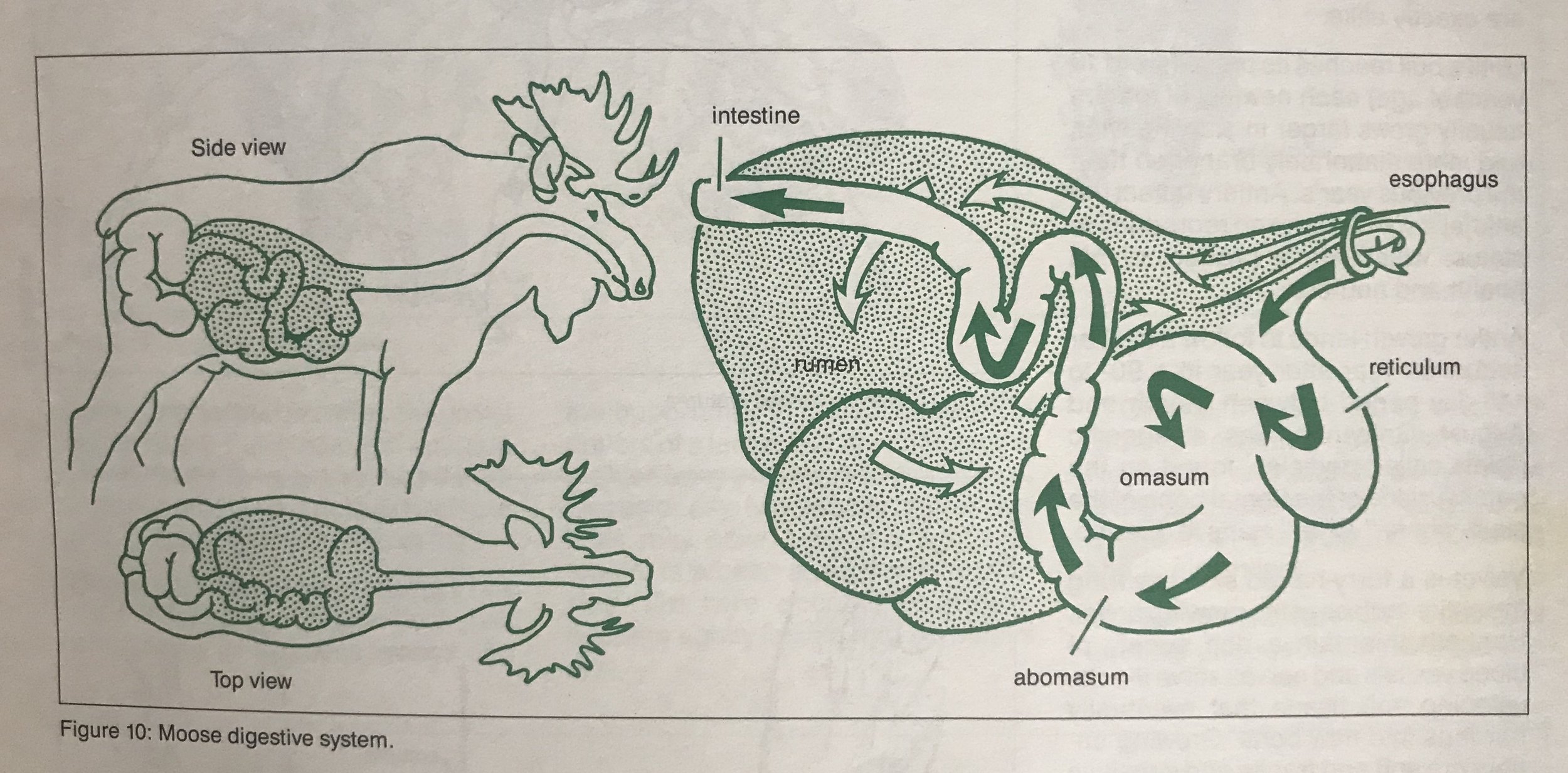

Digestion : Using only lower incisors, Moose rip succulent plant parts such as leaves, early shoots and new green woody growth from their stalks to chew lightly with their molars and swallow them quickly. The masticated plant debris then passes through the esophagus where it then enters the first of four chambers in their stomachs. The first is called the rumen, and this is where the assistive bacteria help the breakdown of plant material, similar to fermentation. Moose actively feed for about an hour often in more open locales where new growth occurs in forested landscapes, but this time in the open can expose them to potential predators. This is why they feed quickly and then they may find a less conspicuous location where they may bed down and regurgitate their the tougher plant materials and chew them once more. Once broken down sufficiently, the Moose swallows again directing the thoroughly masticated plant materials to the reticulum and the omasum where much of the water content is removed. Following that, the materials are passed through the fourth chamber, the abomasum, where the process of absorption of nutrients in the blood begins. This last section of the Moose stomach is comparable to our own.

Scat : As waste is removed from the body it can vary in appearence depending on what was consumed. Wetter, succulent, less ligneous material can appear as softer amorphous plops, similar to Cattle (Bos taurus) patties, or as blobs made up of compressed pellets. If the Moose has been consuming tougher, woodier foods, the scat appears more like pellets, similar to Deer scat, but much larger. This appears more in Winter.

I also learned that you can look for specific features in the scat to help sex the Moose who dropped it! When looking at the Winter pellets, look at the size and shape of the pellet. calf pellets are small, and cow Moose pellets are usually narrower and longer in comparison to the bull Moose. Bull Moose scat tends to be blockier, squatter and fatter. Elbroch and McFarland (2019) provide an equation from MacCracken and Ballenberghe, (1987) . Here is the exact text as they have made it as clear as possible already :

To estimate the volume, measure pellets three times in millimetres (the length, the width, the second width perpendicular to the first measurement), and then multiply the three numbers together. Take the volume and multiply by 1,000; adult females tend to range 8 - 8.5, whereas males range 8.1 - 11.8

I wish I knew this last weekend, and we could have tried it out while we were in Moose country. Next time…

ofAmerican Marten (Martes americana)

Diet : Varied. Mostly consumes voles and small mammals like Squirrels, Eastern Chipmunk (Tamias striatus), Snowshow Hare (Lepus americanus), Shrews, but also small birds up to the size of a Grouse, snakes, insects, and fruit. Note the Vibernum and Aralia seeds in the last photo of the gallery above.

Dental formula : I 3/3, C 1/1, P 4/4, M 1/2 = 38

Digestion : Simple digestive system with a relatively large stomach. There is no cecum. Martens do not digest plant matter completely. Instead, traces of skins and seeds of berries they have eaten can be found in their scat.

Scat : Meat scats are very twisted, ropey, narrow, with tapered ends, often containing short hairs, sometimes bone fragments. Fruit scat, which includes skins and seeds (in Summer months). Tend to fold over or in a semicircle. Scat is often left on elevated surfaces along trailways.

In one study I checked out (Hickey, 1999), it was suggested that seeds which pass through the digestive system of Martens can help in the spread of the plants and that the seeds themselves pass quickly though the digestive system, taking only between 4.1 - 4.8 hours.

Another study looked at the seasonal and sexual differences in Marten diets in Northeastern Oregon. They looked at how often prey items were found contained within 1014 scat samples from 31 radio collared Martens during a Summer and Winter. Here are some of the top species found in the scat:

Vole (Microtus spp.), Southern Red-backed Vole (Clethrionomys gapperi), Unknown Vole, Deer Mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), Unknown Shrew (Sorex spp.), Unknown Chipmunk (Tamias spp.), Northern Pocket Gopher (Thomomys talpoides), Coast mole (Scapanus orarius), Bat (Myotis spp.).

While some of these species do not live in Ontario, there are similar species which may fill a similar dietary niche for the Martens here. I wonder how the Marten got the Bats?

Black Bear (Ursus americanus)

Diet : Truly omnivorous, but seems to consume mostly plants. Spring usually means new shoots of grasses and forbs and also thawing carcasses. May even cannibalize cubs. Summer diet consists of fat, sugar and protein rich foods to bulk up before Winter hibernation. This includes foods such as Blueberries, Raspberries, Chokecherries, and can also include nuts and spawning fish where available, as well as White-tailed Deer and Moose fawns. Autumn diet can largely consist of acorns, Apples, Grape and most other ripe and ready fruits. Black Bears are often found scavenging at dumps and roadkill drop off areas. Mostly forages during the day.

Dental formula : I 3/3, C 1/1, P 4/4, M 2/3 = 42. Incisors and canines used for holding, tearing and slashing prey. Flat, broad back molars used for grinding plant matter. I have read, but do not remember where that Black Bears large canine teeth are disproportionate to their mostly frugivorous and insectivorous diet and could be evolutionary remnant of early ancestor of the Black Bear who was more of a consumer of meat.

Digestion : Black Bear digestion is roughly 10x the length of the animal’s body length. It is a simple digestive system where the length of the intestine is doing much of the absorption of nutrients. The digestive system of Black Bears is proportionately longer than other carnivores, and shorter than other herbivores.

Scat : Varies depending on diet. I have found thick amorphous splats full of digested berries, though they can also be tubular and full of undigested seeds, both deposited randomly along their trail. Scats of fur and bone and thick fibrous roots often appear segmented yet linked. Scats can build up at repeatedly used beds, large kills or carcasses where the Bears repeatedly return.

The third photo above, Black Bear scat from Point Grondine in 2022, was collected and has been stored in my fridge in hopes of finding a permanent location to be released and watched to see what grows from the seeds contained within.

Again with this write up, similar to the last, I am finding that my questions are going unanswered. I would like to know more about how the digestive tracts of some of these mammals work. I have reached out to some other naturalists I know in hopes of getting more leads on where to find this info, but for now, it’s a waiting game. Please check out the list of resources and bibliography below.

To learn more :

Mammal Tracks and Sign by Mark Elbroch and Casey McFarland. Stackpole Books, 2019.

Scat Finder by Dorcas Miller. Nature Study Guild Publishers, 2022.

The Wolves of Algonquin Park: A 12 Year Ecological Study - Monograph by John Theberge and Mary Theberge, 2004 (pdf download).

The Moose in Ontario: Moose biology, ecology and management, edited by Mike Buss, R. W. Truman. Ontario Federation of Anglers & Hunters, Ontario, Ministry of Natural Resources, 1990.

Morphophysiological Specialization and Adaptation of The Moose Digestive System by Reinhold R. Hoffman and Kaarlo Nygren. Alces Journal, 1992. (pdf download)

An Evaluation of a Mammalian Predator, Martes americana, as a Disperser of Seeds by Jena R. Hickey. Oikos Journal, 1999.

Seasonal and Sexual Differences in American Marten Diet in Northeastern Oregon (pdf download)

American Wildlife and Plants : A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits by Alexander C. Martin, Herbert S. Zim, Arnold L. Nelson. Dover Publications, 1951.

The Tracker’s Field Guide by James C. Lowery. Falcon Guides, 2013.