Tracking Journal 2021.11.27

We had just finished part of our climb up Old Baldy, maybe a quarter of the way to the top, just finished checking out some pretty clear mouse tracks, bounding across our trail when we all sort of slowed and stopped. We knew something was a little different about the tracks, but it took a second to register. The trail was pretty clear, though not as crisp as some of the others we had seen. Perhaps that may have indicated some sense of age… Perhaps the air was cooler when the animal came through and the snow was a little more powdery? Perhaps the animal had come through during the evening the day before or maybe during night?

There were five toes with four pointed fairly forward, but one further back towards the metacarpals. This lower toe is kind of like my thumb, set lower back towards the wrist than the rest of my fingers. That would mean that the image on the left in the gallery above is from a foot on the left side of the animal’s body. The next image shows the four tracks within a group, and if I am reading the pattern correctly it is a right front, right hind, left front, left hind. I don’t think they fell like this chronologically, but instead they likely fell like this : right front, left front, right hind left hind. Complicated, but interesting to consider.

The next image shows the 2x2 lope where the front tracks land first, then just as they push off, the hind tracks land in the exact spot where the fronts just were. The shape of the tracks along with the loping gait pointed to a family of animals, and I was hoping for but wasn’t sure of one in particular.

I had only tracked Fishers (Pekania pennant) once before, but the trail was pretty snowed in. That particular trail had no details in the tracks, only slight depressions in the surface of newer snow which had covered and nearly hidden all trace. This time was special though. I could make out small clear sections of individual tracks and as I moved along the trail all the small clear portions came together to help me imagine an intact and clear track. It was like an animation in a flipbook or something like that but the image wasn’t moving. Instead I was developing a search image in my mind for what a Fisher track looks like.

I guess I got caught up in the excitement of the trail that I didn’t end up getting down and taking any measurements of the individual tracks, and the notes I did take were actually pretty poor. It reminds me of when I see an animal in the wild, I am usually so caught up in the “wow, there is an animal” sense of awe, that my observational-precise-analytical mind gets put off to the side. The gift of just being in the moment is important and special and allows me to be in present to the sheer wonder and joy, but there is also a part of me that wants to be taking better care to pay closer attention to and recording the details, like individual track measurements before moving on to the next thing. I did note that the tracks looked big. Bigger than I really expected for Fisher tracks, and it turns out that this might be because the Fisher could’ve been male. According to our conversation in the field, and Donna (Naughton)’s book The Natural History of Canadian Mammals, male Fishers are larger than females, with males weighing in at 3.5 - 5.5 kg (7.7 - 12.1 lbs), with exceptional individuals up to 9 kg (19.8 lbs). Females can weigh 2 - 2.6 kg (4.4 - 5.8 lbs). Male length is 90 - 120 cm (35.4 - 47.2 inches) and females coming in at 75 - 95 cm (29.5 - 37.4 inches), so there can be a considerable size difference.

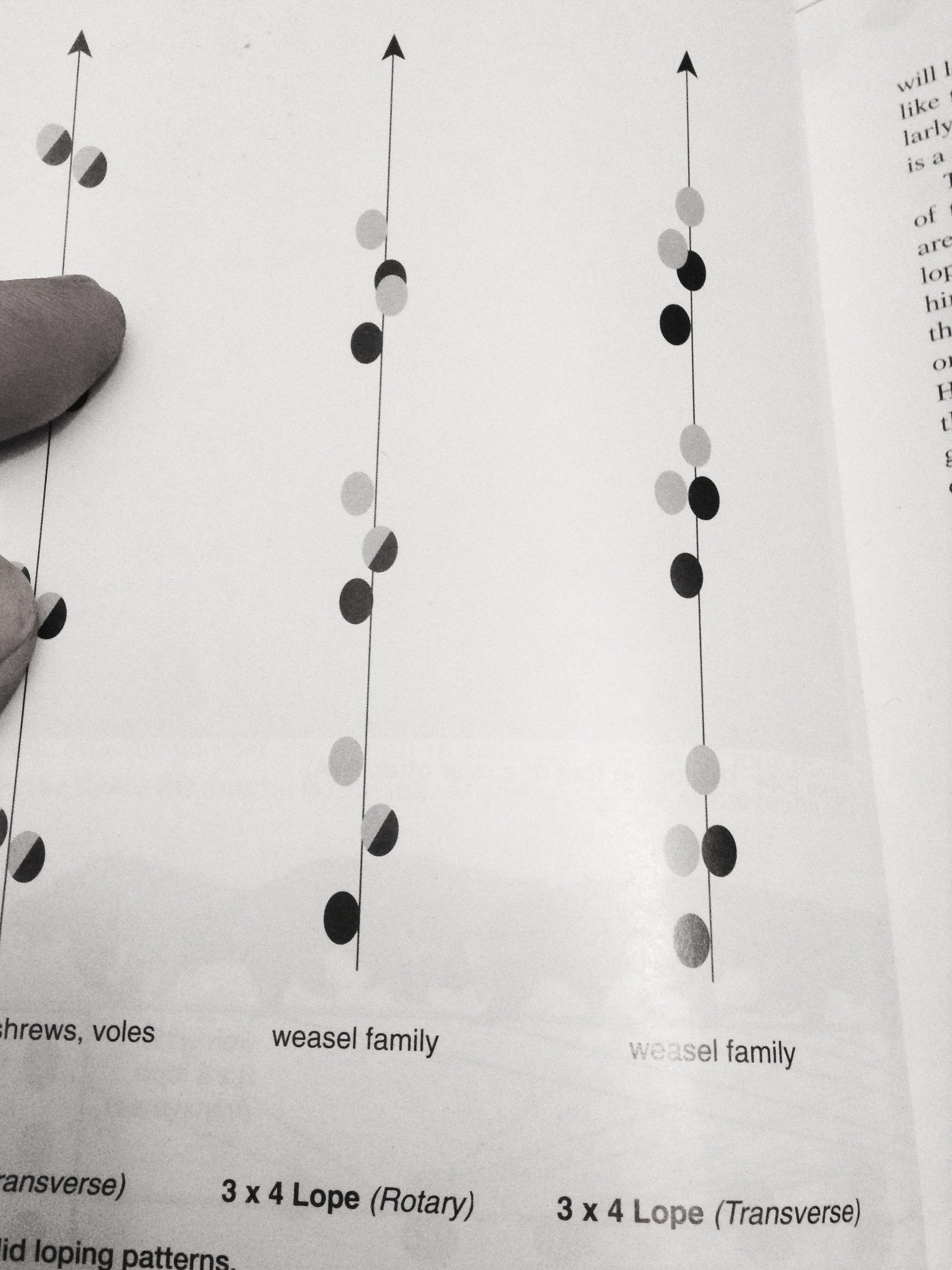

Dark spots are fronts, grey spots hinds.

I stayed back with Alastair as he took notes and I began looking for other sign within the tracks of the Fisher in search of some new info. I looked at the differentiating gait as the animal came from a steep climb, a 2x2 lope, and then, if I remember correctly, the next gait on the trail I could see was a 3x4 lope, which is when a front and a hind foot land either in the same space, or beside one another, making it look like there are only three tracks instead of four. This may be better explained with the help of a diagram from Mark Elbroch’s Mammal Tracks and Sign.

We followed the Fisher as they made their way up the hill, loping through the Eastern White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) trunks. As we followed some folks tried to note the changing gait, and others were looking at the other tracks which seemed to crisscross over our quarry’s trail. I was looking for encounters or particular events, moments of interest which drew the Fisher’s attention. I wanted to see what he may have been looking for, anything he was in pursuit of. One event which stood out for me was the scent mark that the folks in the front had come across while I was still back with Alastair. Folks had noticed that the Fisher’s trail had split. With his legs spread, he “rode” a small piece of wood, rubbing his butt along the length and deposited some scent on to the elevated wood. I couldn’t even see it at first, and Michelle had to point it out to me. Sometimes Fishers scent mark with urine or secretions from anal glands. Just judging from the colour of the scent mark which the Fisher had left behind, I would assume it was from the anal glands, but regardless of which I couldn’t smell it too well.

The Fisher had straddled the snow covered log and their tracks were on either side.

Note the thin pale brown line of scent deposited on the snow covered log.

When I saw this sign on the log, this scent marking technique I got extra enthused. I wanted to keep on the trail and see what came up next. Others were taking notes and moving along the trail at a slower pace, but personally I was stoked and ready to follow.

“You on the Fisher?” Alexis called out.

“Yup.” I didn’t look back, but just kept my eyes on the trail as I ducked through the slim dead boughs at the base of the Cedar trees. I imagined the lithe animal, fierce and silent, flowing over the snow covered rises and shallow hollows along his fairly direct route heading generally Northbound. What drove the Fisher? Was it something he heard, or smelled or saw? My hope was that the trail could inform this a little more, but that so far the answer had to lay ahead of me, a notion which kept me following fast.

I followed the trail up to a small opening in the canopy where when I came around a Cedar like any other at the edge of the clearing I stopped quick and got down on my knees. In front of me was a wide trail with a yellow stain in the snow. Some sort of urine deposit! I obviously bent over the yellow stain in the snow and sniffed quick. It was urine for sure, but instead of what I would have imagined it smelt waxy, and a little like the Eastern White Cedars which surrounded the clearing. I looked at the trail for a moment confused. The urine deposit I was sniffing was situated within a heel print of a different animal. Within the heel print, and adjacent to it, I noticed two crinkly hairs and picked one up. As I did I looked up the trail as well and then back at the hair and then down at the urine in the heel print in the snow in front of me. I was no longer just tracking the Fisher, but there was also a Porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) in the picture.

The waxy smelling urine comes from the Porcupine and all their consumption of the White Cedar. The smell changes when they start eating more Hemlock, but the spicy wax is definitely Thuja. The hair? Porcupines lose hairs all the time. They have so much of it. Four different kinds of hair actually. (1) Long coarse guard hairs which grow between (2) the quills (modified hairs) guarding the warm thicker, shorter (3) undercoat hairs closer to the skin. Finally there is also (4) the vibrissae, or the whiskers, which also hairs.

The big sign that gave all the clues context was the look up the trail towards a big wolf Sugar Maple (Acer saccharum) tree with a bit of a den at the bottom. Just outside this den was some tell-tale scat which had spilled out from inside the hollow trunk where some of our tracking party had discovered the Porcupine in question, head tucked up higher up the trunk with their tail hanging a low as a fairly clear warning to any potential predator who may feel inclined to harass them. I was noting all of which was going on and folks were all around picking out their own clues, making deductions, asking questions, and sharing with each other what they were seeing. I was lucky to get to sit in the midst of most of it and take it all in. Here is what I could piece together from everyone’s discoveries.

The Fisher had been loping through the forest the evening before, seeking whatever pulled them, and happened to run alongside a Cedar tree with the scent of a Porcupine nearby. The Fisher may or may not have noticed too much beyond a scent. The tracks didn’t tell me much, but maybe I just couldn’t read them. From what I did see, the Fisher crossed over the Porcupine trail (which led the Porky from the den to a nearby Cedar) and then kept on into the woods. Meanwhile the Porcupine was probably up the Cedar (or at least had been recently as the bark was all roughed up by their climb), or tucked in the den as we had found them, generally secure from an investigating Fisher. Later in the night, when the Fisher passed, the Porcupine crossed the trail once or twice more, muddling the Fisher tracks, eventually making their way back to the Maple den.

Fishers and Porcupines have a pretty unique relationship. Fishers are one of the only active predators of Porcupines, meaning they specifically go looking for them and do not just rely on them as emergency prey. The Fisher hunts them down and when the they find the Porcupine, the weasel will circle the rodent, and keep circling. The Porky will keep turning around and around trying to get their quilled tail between the weasel and the rest of their body. But the Fishers are fast, and low. Their faces, and mouths, are on the same level as a Porcupines face. When the Fisher sees a moment’s chance, the Fisher will quickly bite the Porcupine right in the face, chomping down with massive masseter muscles trying to get in a strong decisive bite. Fisher bites have been known to crush a Porky’s skull. If the Fisher gets that good bite in, then it could be a quick death for the Porky, but I would be it’s rarely that easy. It like takes many rounds of circling and biting when the chances arise, slowly tiring the Porky, wearing them down, until able to get that big bite in, or the Porky inevitably bleeding to death from the multiple wounds. This isn’t what happened between the Fisher and Porcupine on the trail I was following, but these are some of the moves they make in their entangled intimate world.

Fishers are such good predators of Porcupines that during the 1960’s and 70’s, Wisconsin and Michigan relocated Fishers into areas where they had been extirpated due to over harvesting (ie. trapping for fur). These same area were under abundant Porcupine pressures as Porky populations were growing beyond the carrying capacity of the forests they inhabited. The Fishers were live trapped in other locations and brought to the Porcupine ‘infested’ forests and released. As result of these reintroductions the Porcupine populations were reduced in some areas by up to 55%. The Fishers feasted!

Fisher and Ruffed Grouse intersecting trails. Canadian quarter for scale (23.88mm)

We followed the Fisher a little longer, watching for more interactions but it seemed that there wasn’t much. The Fisher was on a mission. There was a spot in the trail where the Fisher trail had been intersected by a Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) trail. The average stride length for the Grouse was about 16 cm (6.3”). The Grouse was seemed to be chill when walking by, not really the behaviour of an animal in close proximity to a predator. We wondered at this for a moment before coming to the conclusion that since there was little to no variation in the Grouse’s or the Fishers strides that they must have came through at different times, with the Grouse likely coming along later, after the Fisher had already passed.

Just a little ways after the Grouse tracks, while still following the Fisher we came across a stone which rose up about 15.5 cm (~6”) above the snow. On the edge of the stone there was a small protrusion which looked a little different than the rest of the rock. As I looked at it I got to thinking that I knew exactly what was going on, but then someone asked a question and I had to rethink it it all.

“Is that a mushroom?”

Could it be a mushroom? Was it just discoloured because it had frozen? Did it appear to be dripping sort of again because it had frozen and lost some structural integrity? Do mushrooms even grow on rocks? I stopped and thought about it, something I don’t do enough, before making the call. No. It was not a mushroom. I went back to my original line of wondering. Was it in fact scat? Was this rock a natural trail marker, a message board in the Cedar forest to help all of the animals keep track of who was in which territories? I stuck my thumbnail into the protruding whatever it was and then smelled my finger nail (sometimes you just have to get a little dirty in this line of inquiry). My assumption was correct. This object smelled like scat. Just as I was coming to the conclusion the folks around me were noting the Coyote tracks. It sounded like there were seeing one or two possible Coyotes which had come from just up the hill from where we were coming down to investigate the same rock that I was investigating. This too lent to the idea that this rock was infect a signpost for the forest. The Coyote or Coyotes were coming down to check out this spot, seeing who had passed by recently.

It was another lovely discovery. It really served the effort of trying to understand the relationships of the occupants of this forest. The story the tracks told, the interaction between the Fisher and the Porcupine, the Grouse, the Coyotes… These were the kinds of interaction I was looking for. I had heard and read so many things about Fishers, but never had I got the chance to follow their trail. I had wanted to see what sorts of relationships this Fisher has with the world around them. I wanted to see through his eyes, to smell where he smelled, to try and feel as he may have felt. While it may not be possible for me to have the mind or body of a Fisher, I can still begin to understand the habits and relations this individual has with the forest they reside within. And for that I am grateful.

Thanks to my co-apprentices, to Alexis for teaching and sharing so much knowledge, and especially to the Fisher for teaching us so much more.

For more info :

Fisher tracks and sign from Janet Pesaturo's Winterberry Wildlife page