Truffles and the Muskrat Pond

We circled up, sharing gratitudes in the parking lot and moved towards the Cedar woods in hopes of finding some interesting discoveries. When I am tracking alone, I tend to move quickly over small things, noting the sign, but not really paying attention to the context. Say, I might see some scat, but I won't look for correlating tracks, or scatches in the substrate trying to cover it up. I may find a bed, but I don't always get down and look for the hair, or take measurements like I might when I have a crew with me. Lately, I've been wanting more and more to be tracking with groups of other trackers who can share those mysteries, conversations, observations and jokes while out on the land. The crew I usually track with is great and we have a lot of insights to share back and forth, a lot of questions we ask each other further propelling our learning, helping each other with the tasks of photographing, measuring and recording what we are coming across. So good to be out with a crew again, a crew of solid trackers who've been at it for a couple of years, is quite rewarding.

The first thing folks noticed were some small Deer (Odocoileus virginiana) tracks, alongside Canine tracks on the underside of a downed Eastern White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) root dome. What I mean by root dome is the half open, half covered structure at the base of the tree which remains partly in the soil when a windblown Cedar falls. This creates a partial shelter where usually, where I am often tracking, there is exposed soil beneath. From what I've observed, because of the depression where the tree used to be water settles there, moistening the soil which becomes amazing substrate to look for tracks. I used to wonder if it was a great spot for animals to get out of the wind or find shelter from snow in winter, but often within the root domes the soil is muddy or just a puddle and sometimes directly facing the direction the dominant winds are coming from.

The Deer tracks measured about 7 cm (2.75 in) long including the dew claws, one set which were splayed and pointed outwards fairly wide, which led us to assume the that particular track was a front foot (it would likely have been difficult for the deer to place their feet in a perfect direct register under the dome). Out from under the dome the stride measured about 22.8 cm (9 in). Both of these measurements learn towards the larger size of things and even though this Deer slid under a low dome (I should have measured the height of the dome) I am wondering if this was the possible medium sized male someone told me they saw the week before? Just a wonder.. no real evidences beyond what I've already written.

From what folks could deduce a Deer went into the shelter of the root dome and came out again, not really staying put or spending any time there. Later the tracks seemed to tell that a Coyote (Canis latrans) came by investigating the dome and then leaving.

I was sitting on top of the root dome, looking down over the shelf of the root dome, peering into the soft muddy substrates below me while folks were figuring the story of the tracks out. While they investigated further, I looked around on top of the root dome and was grateful that I did as I realized that I had narrowly avoided putting my hand in a moderate pile of Raccoon (Procyon lotor) scat.

Raccoon scat - can you tell what they ate?

The scat appeared to have three segments, possibly from three meals, but seemingly came out all at once as there where no pinch points where the sphincter would have closed and pinched off the scat into pieces. Instead it looked like one long piece which had folded slightly as it landed. The scat was moist and well contained within itself so I assume it was fairly fresh. I wish I could guess at the contents of the scat, but all I could offer is the Corn, either just about ready to harvest or just ready (according to new Corn sales in our area at market stands). I would love to get better at seeing what has been eaten by looking at the colour, texture and shape but that would take a lot of time breaking open scats at different times of year and trying to find as many poorly digested materials as I could, but this is problematic for a couple of reasons. Firstly, somethings breakdown better than others in a Raccoon's digestive tract. A meal of a fresh kill, with soft organs and minimal bone or hair would digest much easier than the hard mineralized collagen structures of bone, or the chitin exoskeleton of a Crayfish.

Raccoon scat, along with many other mammals, birds, and reptiles can carry different parasites or harmful bacteria which can be transmitted to people through handling or breathing in particulate from dry dusty scat. It's always good to be careful around scat and, now more than ever, wash your hands after touching any scat. In fact, best not to touch it at all. I like to use two sticks for prying apart and looking at what the animals have eaten. Examining scat is a pretty worthwhile activity for learning about different animal ecology so despite the possible risks it is well worth getting in there.

Remains of a Twelve-spotted Skimmer (Libellula pulchella)

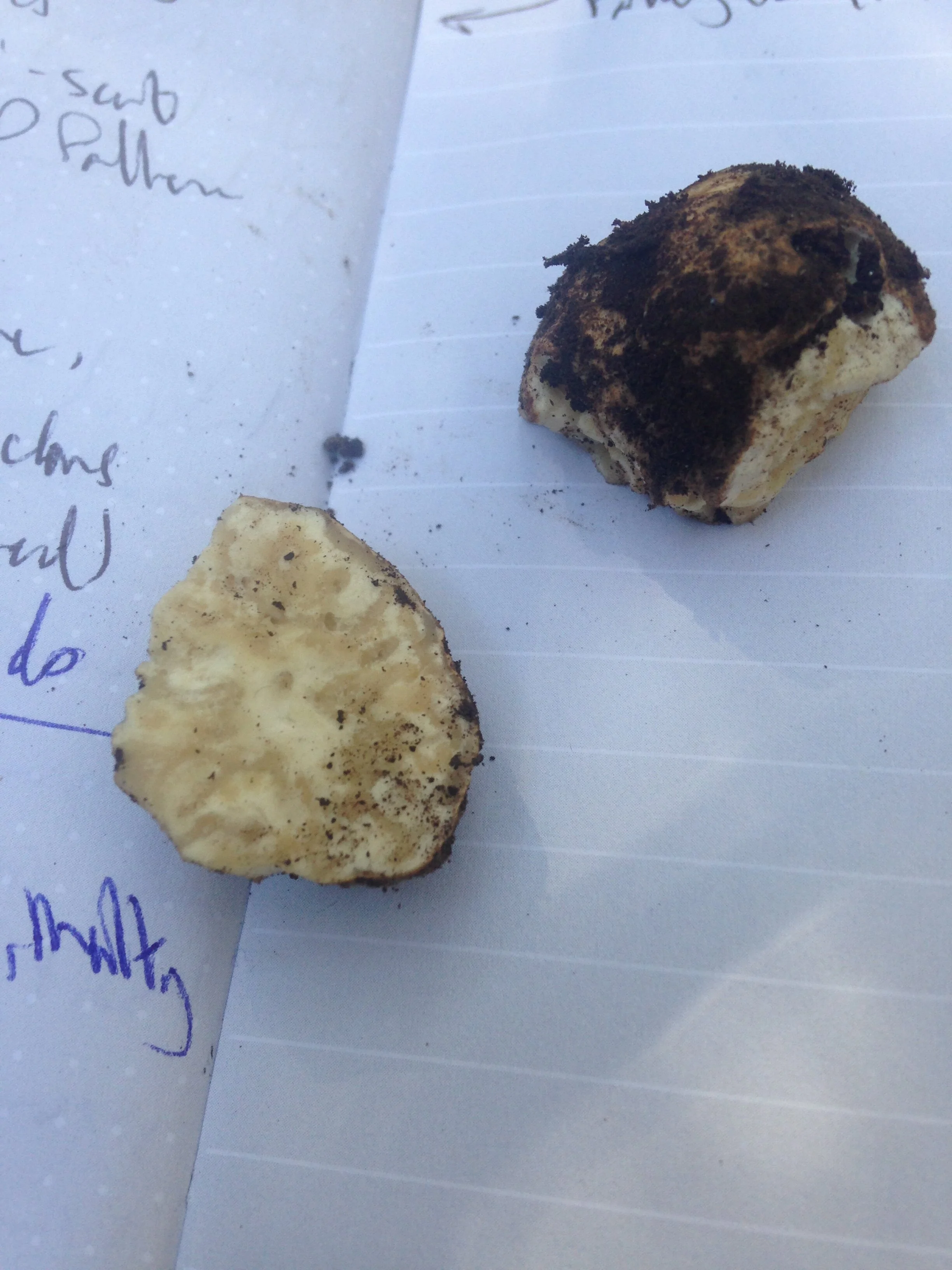

After we had noted the scat, Deer and Coyote tracks, we moved on ever so slightly. Some folks were looking at the remains, mostly just the two left wings, of a Twelve-spotted Skimmer (Libellula pulchella), and others were beginning to investigate a small mudflat, with Coyote, Domestic Dog, and Deer tracks going through. I got distracted and went looking about at the base of more (rooted) Cedars, just to see if there was more Raccoon sign (they often deposit at the base of trees). As I walked I did notice a small brown ball with white scrapes dug into it. The scrapes appeared to be incisor marks, and I assumed a Chipmunk or Red Squirrel had left them. As I looked closer I could even see the discarded scrapings littered about the small brown not-quite-a-sphere. I picked up the brown spheroid and tested its denseness between my fingers, and though it gave slightly, it seemed pretty solid. I smelled the ball and though I had never smelled one before, the word “Truffle” ran through my mind. I called over to the group I was with and asked if anyone knew what a truffle looked like. Steph called back that she had seen the exact object I was looking at and also wondered if it was a truffle. I smelled it again. It had a warm nutty and earthy envelope, with slight “shiny blue metallic” prongs woven within the definite fungal aromas. It was about 2.3 cm ( in) in diameter but I didn't take much notice of the weight, definitely no more than a canadian 25 cent coin.

Eastern Chipmunk foraged on a truffle.

Steph asked if she should take a bite with the same look in her eye as when we both tasted the Moose Urine back in Algonquin park in February (that's a whole other entry), and I think before anyone could say otherwise, not that we would, she nibbled off a piece. She told us it tasted truffly, and fungusy, meaty in a way... and I can't remember what else. I didn't try it until I got home and I had seen that Steph was safe and fine throughout the rest of the day. Also when I got home I tried to look up the species. Danielle had mentioned “Tuber” as the possible genus when she was looking it up on her phone so I started there. It turns out there are a few Truffles in the “Tuber” genus, and the two possibilities I am going to put out there for the one we found (and I am in no way a mycologist) are Tuber canaliculatum, commonly known as Appalachian Truffle, or Tuber lyonii, the Pecan Truffle. These two species can be found in Southern Ontario and up into Southern Quebec. I'm going try and describe what I've learned about the Pecan Truffle here, because I knew nothing about truffles before finding this one and want to share with others in case they too, know nothing about Truffles.

The Pecan Truffle (again Tuber lyonii) is a small fungal fruit that grows underground. It has a light yellowy tan-brown outer skin (peridium) and can be fairly rounded and smooth or lumpy and irregular. The when harvested mature the inside of this Tuber has white marbling within the brown interior. They can grow up to about the size of a golf ball, but is more commonly found to be between .5 – 4 cm across. Again, the Truffle is the fruiting body of an underground mycellium, and being underground makes it difficult for those spores to spread. So instead, Truffles give off their specific odours which attact animals who dig up the Truffles, eat them, and disperse the spores through their scat.

Tuber lyonii has relationships with different kinds of trees all along the Eastern half of the continent including Pecans (Carya), Oaks (Quercus), Hazelnuts (Corylus), and even Basswood (Tilia). The roots of these trees form a mutually beneficial symbiosis with Tuber lyoinii along with other fungi. This relationship is known as ectomycorrhizal symbiosis. My friend Matt pointed out to me that since Truffles are ectomycorrhizae, it means that they grow over, around, and between the cell walls of their host, versus an endomycorrhizae which grow in and through the root tips and cell walls of their hosts. The trees who are in relationship with the Truffles tend to have better nutrient uptake, along with being given growth hormones produced by the fungi. The roots also have improved protections from pathogens as the fungi act as a living, fighting barrier between the pathogens and the roots. The fungi themselves obtain needed carbohydrates from the trees, carbohydrates which the mycellium cannot produce themselves.

A point that caught my attention was that when reading about the mature Pecan Truffle, some authors noted that they smell “nutty and earthy” just as we had described in the field. Other Truffles have been described as smelling cheesy and meaty – I didn't get any cheese smell on this one.

We eventually moved a little towards the SouthEast and came across some sort of bird dropping which I couldn't tell you much about. I can tell you I had seen a similar mess on the ground in a forest near to where we were tracking, but across and upstream along the river. The first day I saw the scat I thought Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) as I had seen a GBH along the river, no more than 4.5 m (15 ft) away the scat pile (or rather piles, as I saw maybe three of them). But this time, when I came across, again, multiple scats, we also found an Owl pellet! Immediately it was torn apart (though we could have taken the time to measure and get an idea of which Owl had left it behind). We looked amidst the remains and there were bones, many bones of all sorts, including what we thought was the smallest scapula we had ever see (on a quick second look we realized what we thought was a scapula was in fact half of a pelvis).

Contents of an Owl pellet

Looking also at the skull we found, I initially, again without thoroughly considering, thought that this was the skull of a Meadow Vole, until I flipped it over and looked at the underside. Meadow Voles have a perferrated palate with tiny little holes dotted along the bone of what would be the roof of the mouth. This skull did not have that. Meadow Voles have long incisive foramina (those holes behind the big teeth - incisors - at the front of the skull) which narrow as they end towards the brain case, where as these incisive foramina stay pretty much the same width throughout their length. The nasals of White-footed Mouse (another possible previous owner of the skull) extend beyond the incisors at the front, but these don't. I have spent a lot of time comparatively going over different details of this skull and have decided that it is likely the skull of a Southern Red-backed Vole (Myodes gapperi). So, still not knowing the species of Owl, I assume they had been hunting in the moist forest habitat, home to our new, now dead, Vole friend.

Next we walked to the Muskrat Pond, which is an old millpond created along the Torrence Creek. with beautiful trunks from old Poplars which grew along the berm which was used to help dam up the water for the millpond. Now these Poplars are dead, and a couple have fallen. The berm is being colonized by Buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica) and Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) but with a few other notable plant species in the area such as Basswood (Tilia americana), Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), and a tall Saskatoon Berry (Amenlanchier) shrub right at the spot where the mill wheel would have ran. While we were there we watched the Green Frogs (Lithobates clamitans) sitting on logs jammed up in the stream. I was watching the frogs and looking for tracks when Steph called from across the lower creek. She had found another mud flat, but this one was wetter than the one we'd seen in the Cedar forest at the beginning of the day, and the wetness meant that the signs of animals passing through may be clearer.

Tracks in the mud

There were Raccoon tracks, Canid tracks, Bird tracks, and more. We discussed the differences between Raccoon and Mink (Neovison vison) tracks and shared about who've seen around these parts. Was it possible that these were Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) tracks? The size just wasn't right. Raccoon tracks are usually a bit bigger, and seem to remind me a little more of small human hands while Muskrat tracks, which I admittedly have only seen a couple of times, are much more... Muskraty? I will write a more detailed discussion of Muskrat tracks soon enough but not today. We collectively ended up deciding the tracks were Raccoon but at this point we were noticing other things too. Something I got interested in was a small set of bird tracks in the mud, about 2.6 cm long (didn't measure the trail width).

Goldfinch or Yellowthroat?

Based on the shape and length, my research leads me to two possibilities : Common Yellowthroat (Geothlypis trichas) or American Goldfinch (Carduelis tristis), both plentiful around the area where we were tracking, and both pretty active this time of year. I couldn't see more than the one set of tracks so there was no way I could measure a stride length, and there was no associated sign to point to what the bird was doing there in the mud. Were they feeding? Do either of these birds feed on the ground? Goldfinches are known to eat insects and glean seeds off of the ground. I saw no sign of seeds being around in that spot, but perhaps they were cleaned up by the possible Goldfinch? What about the Yellowthroat? Spiders, seeds, and occasionally known to glean off the ground. Their track sizes are similar, Yellowthroat being about 2.4 – 2.8 cm, and the Goldfinch is 2.5 – 2.8 cm (both taken from “Bird Tracks and Sign” by Mark Elbroch and Eleanor Marks)... so really, I just can't tell. My answer for now is going to be to just go back to the Muskrat pond and hang out and watch.

We decided it was time for lunch so we headed back to the other side of the stream and sat about and ate. 4 humans amid the noise and bustle of a late woodland summer creek. It was lovely. After about a half hour we managed to head off toward a Pine plantation of mostly White Pines (Pinus strobus) but some others as well. I think the next thing I remember pouring over were some scattered Northern Cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) feathers and a couple of bones. In fact there were pieces of the bill! Upper and lower mandibles, likely the hardest, densest parts of the body. We wondered for a while who might have got this bird, and where they had come in for the attack from? Was it an aerial predator? A ground predator? With no proofs, but guesses based on location, what was left behind, and the fact that it was a Cardinal... I would guess a Cooper's Hawk (Accipiter cooperii), or as I have been calling them this past week, Wood Hawks (I have even given them a new binomial : Accipter sylvestris). But I can't truly know, I am just riffing on this one, and really the not knowing has been encouraging me to check out more Pine forests since the day we went out. I've even found a couple Wood Hawk feather! Oh, and another reason? As Adrian, one of our fellow trackers was leaving, he saw a pair of Wood Hawks in the same small stretch of woods. Just another small clue.

We meandered a little longer through the Pine plantations into the narrow meadows of Goldenrods (Solidago sp.), Tamaracks (Larix laricina), and assorted grasses I don't really know. We encountered Pine Sap (Monotropa hypopitys), an American Dagger Moth (Acronicta americana), and a couple other strange things, like a pile of Deer hair looking like a Deer got it's winter butt shaved or something. Was it preening, or reaching back and pulling out old hair in mouth fulls and dropping them on the ground? Is that a thing? We kept on through the woods, and out again, and through and out. Coyote Scat with small bones within, a ton of Turkey Feathers, and another kill site of some sort of black and white bird. There were tons of Black-Capped Chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) around but the feathers were a little large to be one of them. Was it a Woodpecker? or some sort of fancy Pigeon? By then it was about 4:30pm and we'd been out tracking since 9am. I was getting wilty as I am now writing all of this. At this point we headed through the thicket to the north and made our way to the train tracks. We followed the tracks back to trail we came in on and headed back to the parking lot where we encountered Adrian once again, just in time for a quick closing circle full of gratitude and stories of our favorite moments of the day.

Thank you to Adrian, Alastair, Danielle and Steph for coming out. It was lovely to share a day of tracking with you.