What happened to this Gull?

It was overcast and 0°C at the time of discovery, with a mean temperature of -1.8°C throughout the day. The low overnight the night before was -3.6°C. `

I was walking up the frozen river with some kids in tow. We’d been out for a few hours tracking Rabbits (Sylvilagus floridanus), Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes), and Gray Squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) when we were on the last stretch and one of the kids pointed to a small mound on the ice.

“Look a Penguin!” I think she’d meant it as a joke, but I took note and walked towards the mound. I had walked along this frozen river the day before and hadn’t noticed a mound on the middle of the river bulging out of the ice. I couldn’t tell what it was at first, but my guess was that a log or branch had broken through somehow. As I got close, I learned it was nothing of the sort.

I don’t mean to be morbid but I love finding dead things to investigate. This sounds strange, so I’d better explain myself. When I come across a dead animal I have an opportunity to learn about the animal more. I can take clear photos of the animal, focus on the parts I may never see while the animal is alive, like the feet, the bill, the eyes (if they are still there). I can check out how the wings articulate, and look at the feathers. If the animal is open, I can look at the internal organs and see where similarities lie between humans and the other animal I am investigating. If the animal looks like they have been eaten somewhat, then I can celebrate that another animal got fed, and perhaps their kin got fed. Perhaps they are taken care of in a time of great need. There is a time for mourning and grief when it comes to death in the wild, but there is also celebration and joy, awe and wonder. I have a lot of awe and wonder for this find.

I pulled out my camera and took a lot of photographs.

As of writing this I have not yet identified the Gull, but I am leaning towards a Ring-billed Gull (Larus delawarensis) because they would be the smaller of the two common Gulls in my area; Ring-bills and Herring Gulls (Larus smithsonianus), the latter of which is larger. I have been posting the photos of the Gull across many internet networks in hopes of identifying which Gull it may be, and a couple of folks have written back. One person mentioned that the bill is too large to be a Ring-billed, but is more likely a Herring Gull. I have not been able to check out any good books, but only quick internet searches. I am continuing along this trail of identification and will update this post if I find anything new.

Update: Ornithologist Matt Iles with whom I have consulted on this question confirmed that it is “100% first winter Herring Gull”.

My more intent focus, beyond just i.d.’ing the Gull is to determine how the Gull died, and then how did their breast go missing, and chest cavity become exposed? I would like to offer simple answers but I think simple, and quick, answers often get me going down paths that may not fit right, so I want to take my time on this and begin with observations, and not judgements and claims.

The bird was on their back when I walked up, head cocked as is shown in the photo, which if they were a mammal I would assume a broken neck, but I do not know birds as well so I couldn’t tell, but I knew the position of the neck looked abnormal. I noticed the feet were intact, pinkish more than yellow (why was I expecting yellow?) and that they were thoroughly webbed. I noticed that the crop from the gull was removed, opened, empty and beside the gull on the ice. I noticed the exposed cavity of the birds breast was still bright red and pink, with no discoloration. There were no smells either or signs of flies or infestation of any kind. Overall, it had the appearance of being fresh, perhaps from that morning or the night before. The body was stiff, but still pliable, though the cold weather could have been preserving the bird well.

Away from the body of the Gull I noticed there were a couple of strewn entire and pieces of feathers, some blood smears and shallow frozen “pools”, and some tufts of feathers still attached to small bits of flesh. There were what appeared to be two rows of drag marks with three lines in each row, likely corresponding to three of the four toes on the Gull.

From here out I want to present the information and inferences I have found or come to in trying to determine what happened. I don’t know if I have any conclusive decisions yet, instead I want to collect all of the mounting fragments of information which will hopefully come together to point in direction I can continue to follow.

How did the Gull die?

I am unsure about this one. I was thinking that this could be a juvenile who didn’t quite know how to take care of themselves through the winter yet and succumbed to the weather. The day before finding the gull the low was around 19°C which could have been quite tough for a young bird. I also considered that the Gull may have misinterpreted the ice for water and slammed down against the ice, killing themselves with the impact. But I think the Gull would be smart enough to know the difference, and the ice had lots of snow on the surface, and was not clear ice, disrupting any sort of “window strike” kind of theory.

There was also a guess of a Fox or Mink possibly taking the bird as they may pounce on the Gull, and grab them by the neck and shake the bird until the neck was broken. I had found plenty of Fox and Mink tracks on the ice the day before finding the Gull and even the day of, but there weren’t any sign of fresh Fox or Mink tracks in the area of the bird. The neck looked flimsy and moved as if it had been broken when I flipped the bird to inspect the neck, but there were no obvious puncture wounds.

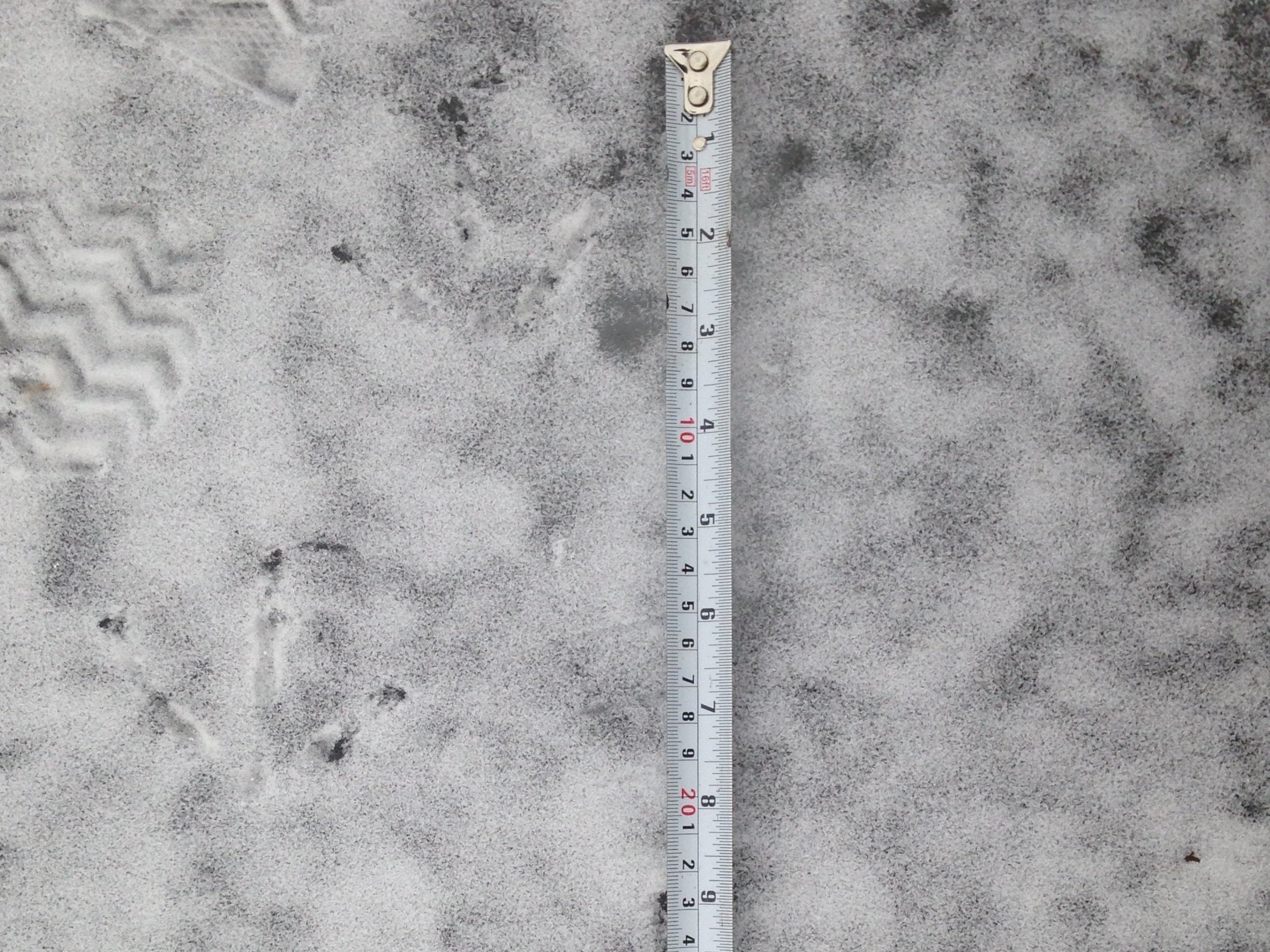

The next consideration were raptors, or birds of prey. There were bird tracks around but I wasn’t sure if they were connected with the Gull or not. Ring-billed Gull tracks measure between 4.7 - 5.7 cm (1⅞ - 2¼ in), and Herring Gull tracks measure 6.3 - 7.3 cm (2½ - 2⅞ in). The Herring Gull would fit with the measurements of the tracks I found but there was no sign of webbing, even when I zoom in and carefully look at the distribution of ice crystals. I looked into a possible Owl, perhaps a Great-horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) but the Great-horned toes are wider or “beefier” or “thicker” to use the language of researchers who I wrote to. The Great-horned tracks would also be too long for the ones I found, coming in at 8.2 - 11.7 cm (3¼ - 4 ⅝ in). An ornithologist friend whom I brought my questions of photos to wondered how much an Owl who likes deep woods would be out in the open hunting Gulls. So, I am going to strike Owl from my list of potential predators.

I also looked up Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) after someone suggested that might be someone to look into. I pulled out Arthur C. Bent’s book Life Histories of North American Birds of Prey (1937) and began flipping carefully through the old browned and brittle pages. Bent included a story from a Mr. Hagar, written in 1936, the year before the book was published, about his observations of a Peregrine carrying a Crow in their talons, setting their prey down and then…

Almost immediately, he [sic] stepped up on the crow, and I could see him tearing off great bites from between his feet - now his head was lowered to take a grip, now he was standing straight up with neck extended, pulling the warm, red flesh with savage gusto-bobbing up and down, feathers flying. For 26 minutes he tore and gulped…

I could see this happening to the Gull, but am not certain. Bent describes that the Peregrines will hunt in the air and knock their prey out of the sky by hurtling at them with great speed and striking them. Could this be how the Gull died? Could these strikes break a birds neck? Or is the neck break from something else? I found this on the Cornell Lab of Ornithology Birds of the World “Diet and Foraging” entry on Peregrines:

Capture and Killing. Captures mainly by grabbing prey with feet (binding) but rarely kills small prey by forcing talons into body as accipiters do. Instead, falcon bites into neck, disarticulating cervical vertebrae and severing nerve cord; even with prey killed in stoop, falcon bites into neck before feeding begins. Prey frequently killed this way while falcon is flying.

Damn. I bet this is to stop any sort of struggling from occurring while in flight or even while trying to evicerate their prey. I have heard of them eating their catch while the prey is still alive as well, but this seems to be a safer bet. A pissed off Gull, or Red-tail (Buteo jamaicensis) would be a dangerous and formidable struggle.

BUT, remembering the feathers with small pieces of flesh at the ends, I present a great paragraph I found in “The Wildlife Techniques Manual: Volume 2: Management. chapter 45 : Identification and management of Wildlife Damage” detailing raptor predation on livestock, specifically fowl like Chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus), and a Gull is like a Chicken, right?. Italicized emphasis is mine.

Raptor kills usually have bloody puncture wounds in the back and breast. Owls often remove the head. Raptors generally pluck birds, leaving piles of feathers. Plucked feathers that have small amounts of tissue clinging to their bases were pulled from a cold bird that probably died from other causes, and was simply scavenged by the raptor. If the base of a plucked feather is smooth and clean, the bird was plucked soon after dying. Raptors have large territories and are not numerous in any one area; therefore, the removal of 1 or 2 individuals will generally solve a problem.

So a Falcon may have knocked the bird out or come across the Gull later. An argument could be made that the bird could be getting cold outside on the ice, but I imagine that might take some time, and the body heat of the Gull may have been retained for a while before dissipating. Maybe the bird was already cold when feeding began, but there is something else getting in the way of this. The pools of blood imply that the Gull was still alive when a bird of prey would have began feeding. A still heart doesn’t pump the blood, but a beating heart does. A bloody pool, and then a smear across the ice would indicate the heart was still beating, the body still bleeding, as the bird of prey began feeding.

I don’t know if this brings me back to square one on the death of the Gull, but I want to take it into consideration. I don’t want to get too excited or discouraged. Instead I want to keep offering more clues and research.

One thing a tracking mentor Alexis Burnett pointed out, as did many others after him, was that the Gull looked pretty clean, in light of having their breast, and internal organs, and viscera missing. I found a paper entitled “Direct and Indirect Effects of Peregrine Falcon Predation on Seabird Abundance” where when detailing the little dead Auklets (Alcidae) they found, they found this to be a common characteristic of the Peregrine kills :

We saw auklet corpses frequently. Those caught and consumed by Peregrine Falcons were characterized by the head remaining attached, and skin and feathers neatly pulled back. The neck, wing, breast and thigh musculature, and contents of the abdominal cavity were consumed. Some of the corpses were almost museum-quality preparations. Beak marks were sometimes visible around the rib cage.

While I found no traces of a ribcage, the rest of this rings true.

I decided that the best course of action to try and get any sort of definite input would be to contact those who have researched and studied hawks and falcons. I contacted Robert “Bob” Rosenfield, Coopers Hawk researcher, and Ed Drewitt, Peregrine Falcon researcher, both of whom I have been privileged to interview in the past. I sent them the all the photos and observations that are shared above, and they kindly wrote back.

Bob wrote back to me on 2022.01.14.

I'd guess Peregrine by length and girth of toes (not Coops which I'd guess to be shorter in length); likely not owl as toe prints suggest toes not as 'thick' as those of owl. Reiterate a guess, but reasonable one -- Ps will take gulls, Coop could but not 'likely' prey.

This was helpful, especially as I know there is a Coopers Hawk in the valley and that was one of my top three guesses.

On 2022.01.14, Ed Drewitt wrote back with

This certainly looks like the work of a peregrine - the way it has been eaten, the discarding of the crop, etc.

I'll check by banding books to see if I can get a foot measurement. For now though I reckon peregrine is a good choice (goshawk is also another possibility although perhaps less likely in the open like this). Peregrines are more likely to sit out and eat like this.

Then on 2022.01.16, he followed up with

Checking one of my banding/ringing books - for peregrine the central toe (not including the claw) is between 43mm and 57mm depending on the race and sex. If you include the claw, then for a female peregrine (which I would suggest is what killed such a large gull) the measurements fit. Middle toe is a similar size for goshawk (and has a longer claw).

Amazing. Deducing a female Peregrine Falcon from the look of the kill site, the size of the animal killed, the habitat where it happened, and the width of a toe. I am incredibly thankful for the help of folks who know a lot more than I do to help narrow down this mystery. Hearing from Bob and Ed, confirming my associated research helps me move on to next steps of looking into local observations of Peregrine Falcons.

In the winter of 2020, a co-worker and I, along with a big group of kids, watched a Peregrine Falcon chasing down Rock Doves (Columba livia) at a former jail about 1 km East of the kill site. It was a thrill to watch the Falcon fly at the flock. They didn’t catch one that time but it was still exhilarating. Much more recently, 2 Inaturalist observations from Jan 2, 2o22, 12 days before I came across the kill site, indicate a Peregrine Falcon was observed downtown Guelph on one of the towers of a tall cathedral, just about 3km West as the Peregrine flies from the location of the kill site. It is likely the same bird that killed the Gull.

There are so many more questions to ask about this mystery, but I know I need to move on. There have been more signs of different animals that I need to research and understand better. Here is a quick list of some of the things I am wondering about:

What is the hunting range of a Peregrine Falcon?

What is the range of total lengths of a Peregrine foot?

How can I age a dead bird in winter when decay is slowed significantly?

How can I tell between juvenile Ring-billed and Herring Gulls?

How often does a Peregrine Falcon need to hunt?

To learn more :

Peregrine Falcon - Birds of the World - Diet and Foraging

Direct and Indirect Effects of Peregrine Falcon Predation on Seabird Abundance

Interview with Ed Drewitt about his book Raptor Prey Remains

Interview with Robert Rosenfield about Coopers Hawks (mp3)