Tracking at Puslinch Tract Conservation Area

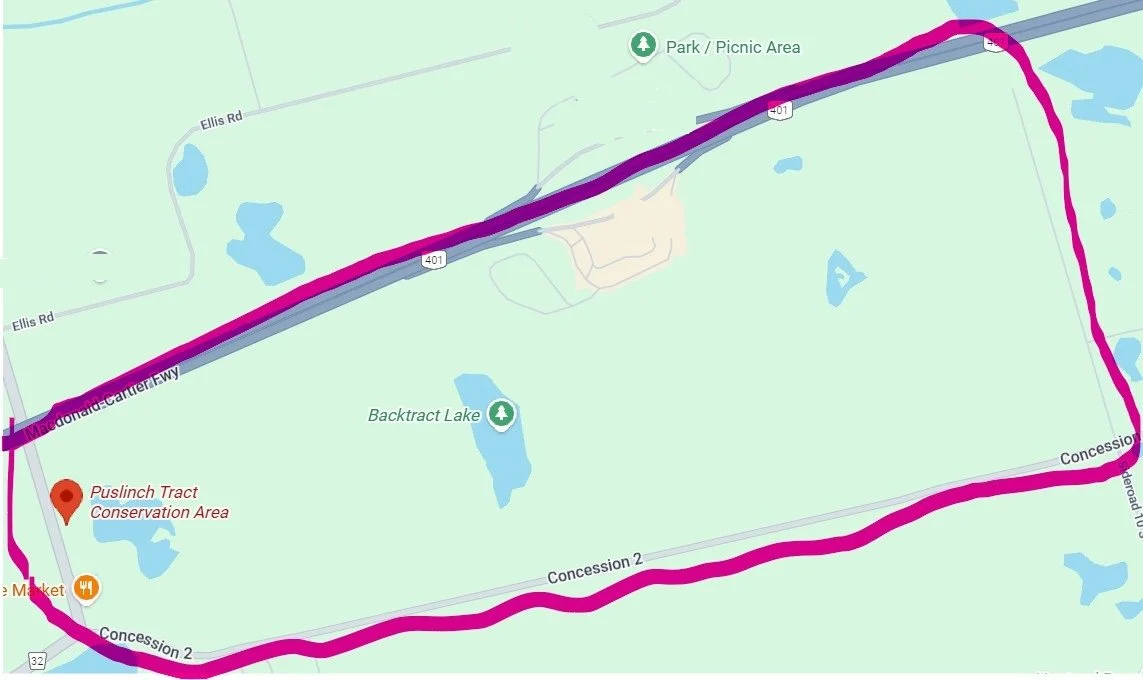

I have been spending the start of my time off climbing, going to yoga and plotting tracking trips to new areas within an hour’s drive of Guelph. I am on the search for different landscapes to explore and potentially encounter new environments I don’t normally get to within or on the periphery of the city. For the past couple of days I have been exploring Puslinch Lake Conservation Tract, and it’s an interesting spot. Bordered on the North side by the 401 highway, East by sideroad 10, South by Concession 2, and on the West by Wellington 32, the long rectangular park seems mostly used by mountain bikers and dogwalkers, and I discovered on my first visit that the park area surrounding the lake is pretty much just that - an off leash dog park. While it isn’t supposed to be, every dog I came across did not have a leash on. I am ok to some extent with this, but the whole West side was fairly void of animal tracks aside from a couple of Coyotes (Canis latrans) and quite a few Grey Squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis). My thought is that the dog pressure is too much for many animals to hang out in the area so they move off to the East end, away from the main parking lot on the West side.

Again the first day was kind of fruitless but one thing that caught my eye was a Baltimore oriole (Icterus galbula) nest hanging in a tree adjacent to the lake on the West side. It was fairly high up so I wasn’t able to get a good photo, but I was a bit stoked as I am really struggling with nest identification and this was an easy one.

Baltimore Orioles have pretty distinct pendulous nests made by the females in May. The sacklike nests are made up mostly of plant fibres such as Milkweed (probably Asclepias syriaca), Dogbane (Apocynum spp.), Grape (Vitus spp.) and various grasses, and are strung up to a branch usually fairly high. These nests are meticulously woven together and quite durable. The inside of the nest is often lined with plant down, wool, and mosses. They often hang around throughout the Spring and Summer of the following year after they are built, and sometimes the female will repair old nests and reuse them.

While most often I see the Baltimore Oriole’s nest usually about 9 m (30 ft) high, I recently climbed about 4 m (13 ft) up a Manitoba Maple (Acer negundo) which was situated at the crest of a large hill overlooking the Eramosa River valley. While it wasn’t 9 m high up in a tree, it would have given the inhabitant a sense of being higher off of the ground. Another note is that I have often read that the nests are attached to downward curving branches, but around here I have never seen that. Mostly upright branches, and often on Maples (Acer spp.) but I imagine any tall growing deciduous tree is suitable for an Oriole’s nest.

On the second day I went, I was headed to a different park and decided at the last second to turn left rather than the planned right and head back to the Puslinch Tract, but to head in to the park from the South off of Concession 2. There is little parking but I found a suitable spot, and went in. My intentions for the day were to find some feeding sign of any sort of animal, and, if possible, find a bed from a Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes), Coyote (Canis latrans), or White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus). If I didn’t find them, that would be ok, but it’s good to dream a moderate dream once in a while.

Immediately I came across what appeared like a planted garden of Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans). It looked like a garden because it seemed like there were no other plants growing in that spot, and the area was entirely littered with short woody stalks with clusters of ribbed yellow fruit attached at the terminal ends. I had taken photos of a similar habit and form in the Summer out near Saugeen Beach except that then the fruit was more pale green and was draped in typical Poison Ivy leaves.

I posted the photos above on INaturalist a couple hours after getting home and the following day when I checked it out, three people had identified the plant as Toxicodendron rydbergii otherwise known as Western Poison Ivy, challenging my identification of Eastern Poison Ivy, Toxicodendron radicans. To be honest, I never knew there was a difference until I saw this, and I am still learning about the difference now. Here are some of the differences between the two distinct species:

Eastern Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

Above ground woody stalk has aerial rootlets

Climbs neighbouring trees and shrubs

Clusters of flowers are up to 10 cm (4 in) long with female and male flowers on separate plants (dioecious). Each flower about 6.4 mm (¼ in) across with greenish white to yellowish green petals.

Fruit are about 4.2 mm (1/6 in) in diameter.

Western Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron rybergii)

Above ground woody stalk does not have aerial rootlets

Does not climb.

Grows up to 1 m (3 ft), but usually more like 60 cm (~2 ft) or so

Flowers grow in in loosely branching clusters 5 - 30 cm (2 - 12 in) long that grow out from the leaf axils. Each flower is about 4.2 mm (1/6 in) across with 5 greenish white petals and 5 stamens with yellow tips.

Fruit are about 3.2 mm (⅛ in) in diameter.

I saw no sign of browse on these stalks though I will check again the next time I return as Poison Ivy is commonly consumed by many bird species. I am not going to include scientific names here as per usual, because the list is already long enough:

Ruffed Grouse, Wild Turkey, Northern Bobwhite, Eastern Bluebird, Bushtit, Catbird, Black-capped Chickadee, American Crow, Purple Finch, Northern Flicker, Dark-eyed Junco, Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Eastern Phoebe, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, White-crowned and White-throated Sparrows, European Starlings, Brown Thrasher, Hermit Thrush, Tufted Titmouse, Warbling Vireo, Cedar Waxwings, Downy and Hairy and Pileated Woodpeckers, and many many others who do not leave in my region.

Mammal consumers include Black Bears, Muskrats, Eastern Cottontail, and White-tailed Deer, and again, countless others who have not been recorded. I am certain Meadow Voles and Deer Mouse are consumers, but just haven’t been recorded yet.

As I moved on, I quickly got on a White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) trail. There must have been three or four individuals moving together browsing on all sorts of different things including Common Privet (Ligustrum vulgare) and Multiflora Rose (Rosa multiflora), both of which stood out for me. I followed the deer for a while as they cycled around amidst odd shrubs and into and through a Pine (Pinus spp.) plantation and into a mixed wood of Sugar Maples (Acer saccharum), Beech (Fagus grandifolia), Red Oak (Quercus rubra) and Hop Hornbeam (Ostrya virginiana). As I trailed the deer it became clear that they were a group and were travelling together. The ranged over short hills and shallow valleys until they came to the base of some Red Oaks. There, the snow was scuffed up and leaves were strewn about. I had seen this once before, up in Lake of Bays in February 2022. This time I recognized what was happening right away.

The deer were digging away at the snow to reveal some of the remnant Red Oak acorns dropped in the Fall. This is pretty cool and the first time I studied this I learned a bit about botany while I was trying to learn about the deer.

Here’s some of what I understand. Acorns have tannins, or tannic acid in them. This is the incredibly bitter flavour that comes through when you try to eat a raw acorn. This tannic acid protects proteins and slows decay and they help to keep an acorn from spoiling before they have a chance to sprout. Some oaks take longer to sprout, while some require a shorter period. White Oaks (Quercus alba), a species and a loose grouping of species with some similar characteristics (like rounded lobes on the leaves for one), produce acorns with less tannin content. These acorns need less protection since they germinate in the Fall and do not need to resist bacteria and fungi for as long before they sprout. Red Oaks, another individual species and informal grouping of characteristics, tend to germinate in the Spring. That means they need more protection over the long Winter, and that protection comes from more tannins. These tannins keep the acorns free of pathogens but also keep them safer from predation by wildlife. That means that while there are milder, not as astringent or bitter tasting White Oak acorns around White-tailed Deer tend to avoid the Red Oak acorns, but once those White Oak acorns run out, or access to them changes, then the deer will take what they can get. It seemed like presently, it was the Red Oak acorns.

I have read in two sources that acorns are the most preferred food of White-tailed Deer in ranges which the deer have access to them. They can comprise 75-80% of their diets throughout the Fall and Winter. One article I read states that acorns “contain more energy than corn, two times the amount of carbohydrates, and up to 10 times the amount of fat”. This is no real surprise as I have been eating acorns for a few years now and they are both delicious and my body feels good after eating them.

Something I have been noticing this year is that whenever I have come across acorns which have been consumed by deer, I see that the deer are very inefficient at extracting the inner nut meat. In the photo above there are three halves with nut meat remaining. This seems to be a near constant sign for deer. It must suck to not have the ability to use your hands to better obtain your nutrients. I wonder if they sometimes go over the area that they have already been in to try and find the nuts they dropped and consume the remainder of the nut meat? I have read that Wild Turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo) may follow the deer around and look for the remaining bits the deer left behind.

As I continued to trail the deer through the snowy deciduous forest I came to four more of these digs created by the deer.

It seems that I had intruded on the signs of a lovely buffet night for the deer, stuffing themselves on the seasons goodness. And as we are known to do as well, the deer I had been following found a high spot just outside of the loose debris of their holiday dinner party and laid down for a quiet rumination.

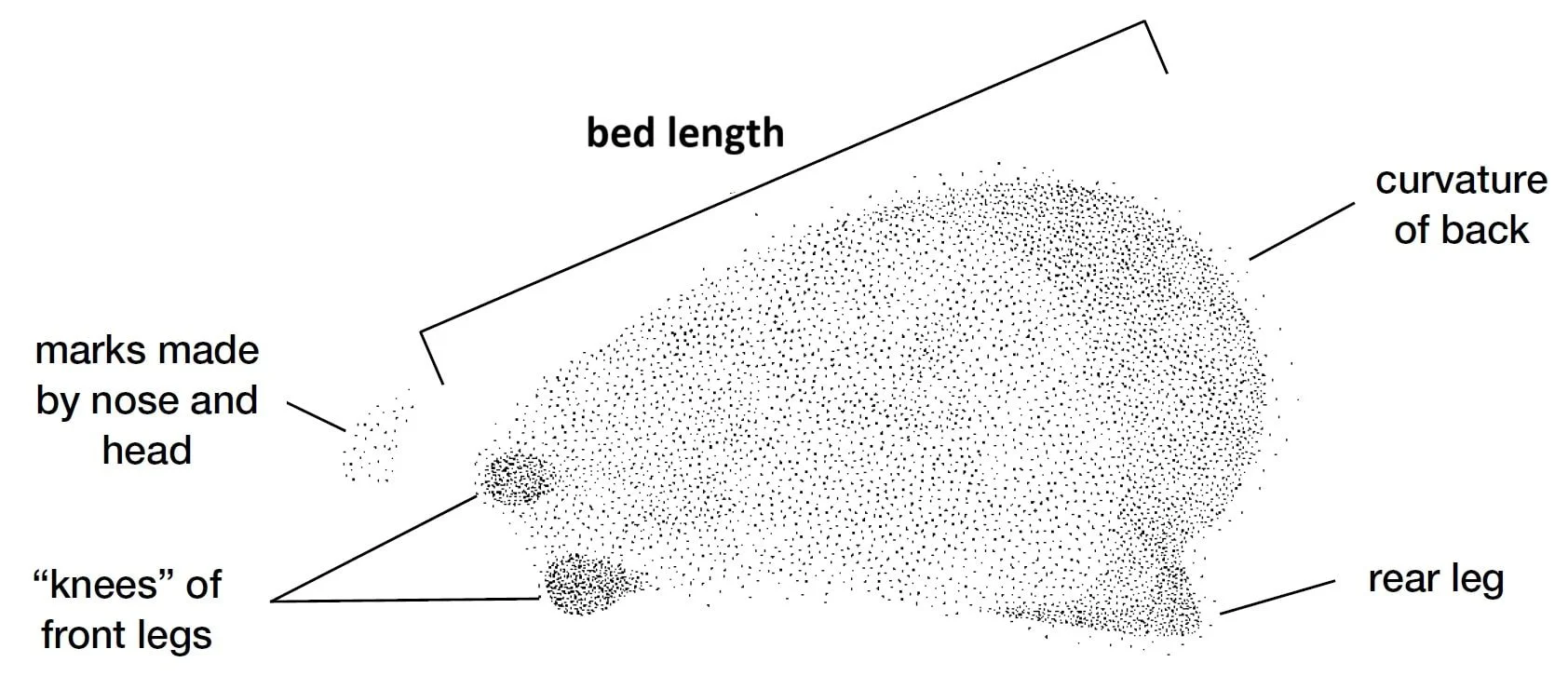

Using the diagram from Mammal Tracks and Sign, 2nd ed. by Mark Elbroch and Casey McFarland, can you make out the same characteristics in the photograph I took?

I ended up ditching the deer trail after finding the beds. I guess I have a short attention span sometimes, but I was happy to have found some feeding sign and some beds, my two intentions I went out with. I ended up walking sort of North-Eastwards until I got on a Coyote trail, which I followed for a short run, and then this trail intersected with a mountain bike trail which I carried on with until I came across an older Red Fox trail. I stayed on the bike trail but followed the Red Fox trail with my eyes, and noticed a long stretched out, grey mass laying on top of the snow. At first, I thought it might have been the fallen web mass from a Fall Webworm Tent Caterpillar (Hyphantria cunea) which had blown off of a tree, but something seemed strange so I went over and looked at the debris.

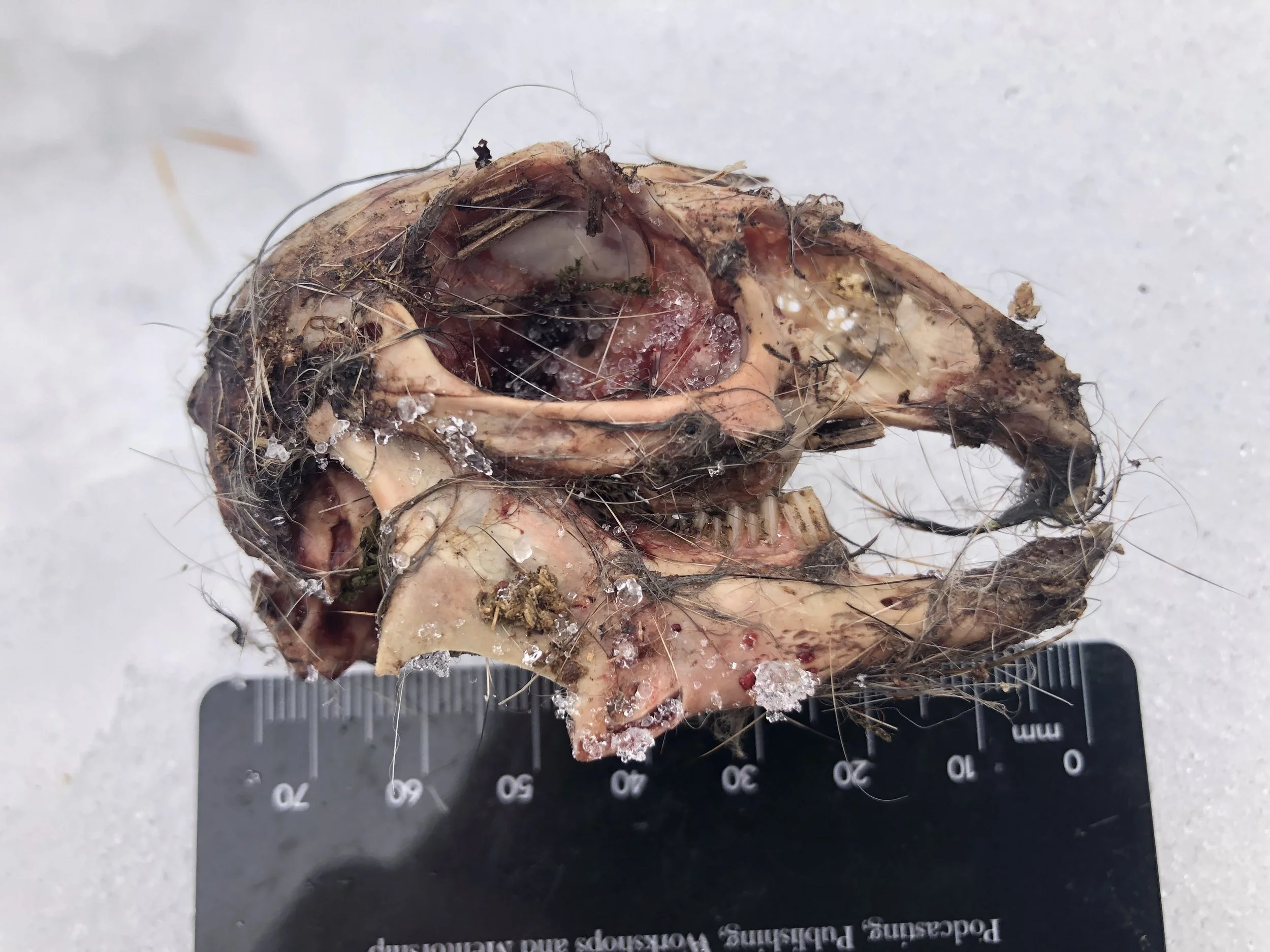

As soon as I walked up to the mess on the snow I knew what it was. I saw the brindled hair, some bones still strung with loose tendons and muscle, as well as a complete skull which declared the species. This mass was the remains of an Eastern Cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) which had been pulled from a cache in the snow a few feet from the carcass. I looked at the cache hole and it reminded me of a Red Fox cache I had found many years ago in Algonquin Park. I believe that a Red Fox may have uncovered the cache and dragged the remains out. I also noticed small paired tracks near by in a long jumping pattern which pointed to a Short-tailed Weasel (Mustela erminea). The weasel likely did not have anything to do with the carcass in the current position, but may have been the initial killer and possible cache’er of the dead Cottontail, but at my skill level, the body was far too fed upon to be able to look for signs of a possible predator.

After finding the carcass I kind of figured it wouldn’t get any better that day so I just wandered a little more. Found my first set of Ruffed Grouse (Umbellus bonasa) tracks of the season and an old shanty that someone had built. I even made it up to the back of the Cambridge OnRoute parking lot, before turning around and heading back to the car.

It was a great outing and I will definitely be coming back to Puslinch Tract.

To learn more :

Peterson Field Guide to North American Bird Nests by Casey McFarland, Matt Monjello, and David Moskowitz. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2021.

Minnesota Wildflowers entry on Western Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron rydbergii)

Minnesota Wildflowers entry on Eastern Poison Ivy (Toxicodendron radicans)

Field Manual of Michigan Flora by Edward G. Voss & Anton A. Reznicek. University of Michigan Press, 2012.

The Nature of Oaks by Douglas W. Tallamy. Timber Press, 2021.

American Wildlife Plants: A Guide to Wildlife Food Habits by Arthur C. Martin, et al. Dover, 1951.

The Deer of North America by Leonard Lee Rue III. Lyons Press, 1997.

Acorns and Deer Management article by Dr. Craig Harper and Jarred Brooke (pdf)