Highlights of Tracking in the Boyne Valley

I have been thinking a lot this Winter about how amazing it is that all of the various species we track can survive such apparent hardships of freezing temperatures, labourious snow depths, and drastically reduced vegetal forage. It’s like turning off the heat in your house, wading through 60 - 90 odd cm (2 - 3 ft) carpet pile, while constantly engaging all your senses to find the perpetually vigilant and furtive refrigerator. Tough times indeed.

So while out the Earth Tracks Wildlife Tracking Apprenticeship program in the Boyne Valley, I had an eye to how some of the animals were making their ways across the landscape, what they may have been eating along the way, and see if I could learn a little bit more of the local ecology here in Southern Ontario .

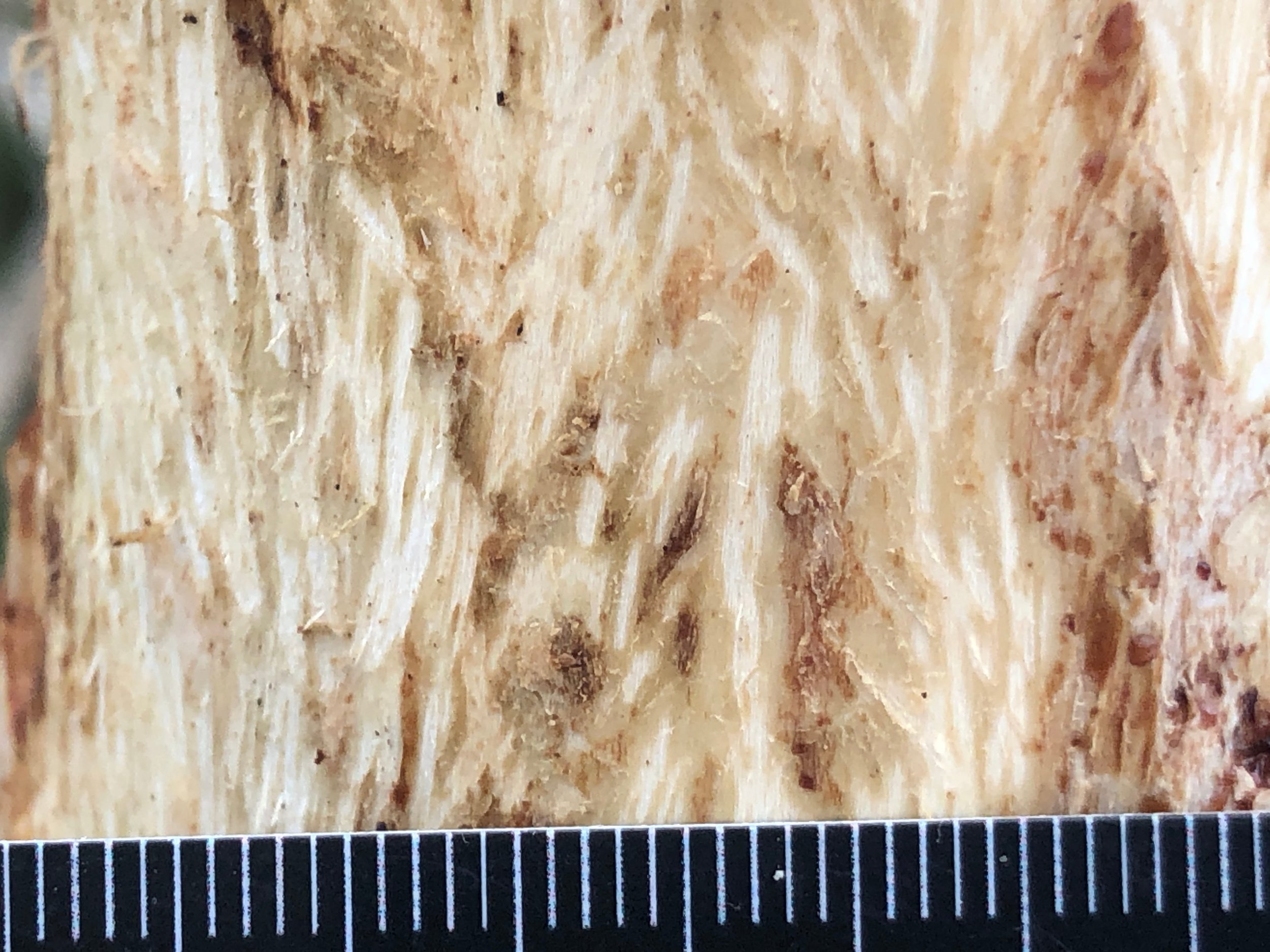

Directly beside the Bruce Trailhead parking lot there was a stand of Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina) shrubs and located between 90 - 180 cm (3 - 6 ft) high along the trunks were sections of exposed wood where the bark had been chunked away and discarded on to the snow below. There were short, mostly vertical grooves left in the cambium layer of the trunks, grooves which were about a third to half a millimeter wide (1/64 in). They appeared to be incisor marks scraping away the cambium layer for food.

From a distance, I could mistake this sign for that of a Porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum), but all of the branches close to the exposed areas were much too thin and fragile to support the weight of a Porcupine and the marks would have been too small for a Porcupine’s incisors. Instead we started to consider other possbilities of smaller animals than Porcupine, even though the signs was high up and the snow pack was deep, it was not as high as the sign. Could it have been from deeper snow pack from a previous year? N0, as this was certainly fresh sign from this Winter. If it were from last year, there would likely be some discolouration at the edges of the feeding area, and some speckled mildew growing on the exposed wood.

Which local species can climb, and feeds on cambium, has tiny incisors? Our minds went to Vole. There are two voles in the area, Meadow Vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus) and the Southern Red-backed Vole (Clethrionomys gapperi), but the habitat gave us some clues. While Meadow Voles prefer meadows, prairies, fields and woodland edges, the area we were in was mostly forested. Sure, we were at the edge of said forests, but thinking of all the clues, we began to lean towards the Red-backed Vole. Who among the two vole species named has smaller incisors? It’s the Red-backed, coming in at an average of .62 mm for the lower incisors and up to .80 mm for the uppers (teeth are measured in millimeters), while the Meadow Voles range between .98 mm for the lowers and 1.25 mm for the uppers. Another point for the Red-back. Do Red-backs climb and feed on cambium? They do climb trees, but feeding on cambium is uncertain. Meadow Voles certainly feed on cambium and I have found dozens of examples of this behaviour, and I would assume the same for the Red-backs. Really though, it would be nice to have direct empirical evidence when observing familiar sign from a species I have not seen making that sign before, or at least read about someone else’s experience of the sign. Some lingering questions remain. Can we be certain it was a Red-backed Vole? Are there any differences in their sign that would help us distinguish them in the future? Do Meadow Voles climb high into trees to feed on cambium? Does either vole species in my area have a preference for Staghorn Sumac? Would the parking lot beside the sumac affect the qualities the voles are looking for? These may never be answered.

We moved across the road and through the Eastern White Cedar (Thuja occidentalis) forest and slipped down a steep hill into an open river meadow dotted with melted out tracks of White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus), Meadow Voles, and Coyotes (Canis latrans). As we walked along these trails we also came across a spot in the snow where there were two Brown-lipped Snail (Cepaea nemoralis) shells sitting at the base of some Goldenrod (Solidago sp.), Virgin’s Bower (Clematis virginiana) and Raspberry (Rubus sp.).

The shells were empty of their creators and because of this it reminded me of a paper I read from 1907 about Short-tailed Shrews (Blarina brevicauda) and their habits of piling up discarded snail shells in Winter. It was a unique paper and the writing a bit dated making the whole thing enjoyable to read (there is a link to the paper below). Anyways, when trying to discover the piler, the researcher found, through interesting means, that the likely species was the Short-tailed Shrew. One sign to look for when finding these piles of snails in Winter is small holes, burrows or tunnels nearby. While it wasn’t exactly clear, there do appear to be holes into the subnivean (under the snow) at the base of the forbs.

I wish now that we had checked some of the shells out better. I noticed one the shells had a smooth cellophane like covering over their aperture, the hole where the soft body of the snail emerges from the shell. This covering is called an epiphragm, and the snails create it with their slime to seal off the aperture to prevent dehydration while they hibernate in the Winter. While I noticed this on one of the shells, I do not remember if this was present on the other shell. I also not remember finding any sort of crunching into the shell around the apical whorl, which is the middle area the spiral of the shell. Crunching a hole in the apical whorl is a common way for Short-tailed Shrews to gain access into the shell so they can feed on the snail within. The shrew may also gain entry through the epiphragm, but if that wasn’t broken either, than perhaps the shrew had simply discarded the shell without consuming the snail?

And while I was a little cautious in this identification because there were only two snail shells, the writer of the 1907 paper found piles with as few as two or three up to a hundred shells discard in a midden pile! I believe my shell pile record would be about 20 or so shells at the base of a Manitoba Maple (Acer negundo) a few years ago. When hunting for snails the Short-tailed Shrew collects them, bites the snails and then caches them somewhere within their tunnel system, and often under logs. The snails cannot escape because Short-tailed Shrews are also one of the very few mammals with venomous saliva, a venom which can cause their small prey to have breathing trouble and circulation issues. It also leads paralysis and maybe even death. It’s pretty cool but also pretty spooky for the snails. I am also wondering if Short-tailed Shrews going after Cepaea snails in my area is unique? None of the papers I looked at mention Cepaea species in relation to Short-tailed Shrew diets In reflecting on this small, possible midden pile, I realize that I must look into the signs we find a little bit more when I find them in the field.

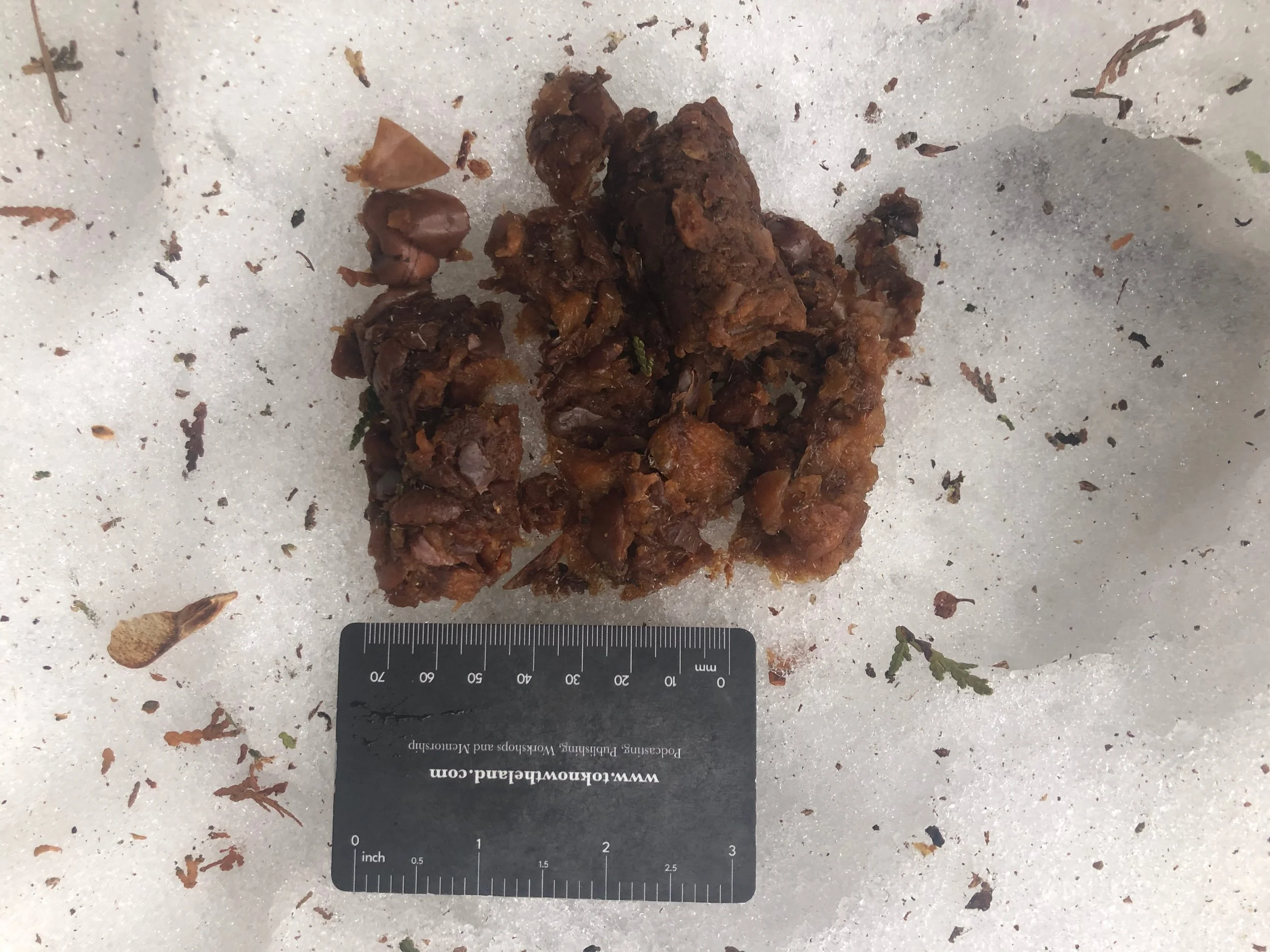

As we moved on, what we had thought earlier had been a Coyote trail proved to be true. The trails were set in shallower snow under the shade of a tunnel of Eastern White Cedars and followed a human trail a little ways up from the river. A short ways into the tunnel of cedars we came across a Coyote scat.

There appeared to be a lot of it as well. The diameters were well over 2 cm (¾ in) and they appeared to be full of chewed up Apples (Malus domestica).

Coyotes eat a lot of Apples. If there are Apples around, and Coyotes around, you’ll find Apples in the Coyote’s scat. When in proximity to human development and habitats, Apples are an easy to find food source that they don’t have to expend a lot of energy trying to run down through deep snow. But I wonder at how much energy is expended in trying to acquire to the Apples, and how much they get in return, especially when the scat appeared as if nothing had really broken down the Apples and little nutrition appeared to be pulled from them? I can’t find much information online about the energetic outputs of Coyotes digging in snow, nor the energetics they acquire from consuming Apples, but what I do know is that Coyote digestive tracts are short relative to humans and herbivores, and the Apples they consume must move through the digestive tracts quite quickly. They must probably consume a large quantity, with little energetic return (based on the observations of the content of this particular scat and many others I have seen). Why then do the Coyotes consume so much Apple if they don’t appear to get much from them? It might just be because it is there, it fills their belly and may even act in a similar way that grass eating does for some other canids - the chunky bits help to “scrub” their digestive tracts and the fibre keeps them regular? I can’t know for sure, but the quick carbs and bit of hydration from an Apple may also be helpful.. but how much do they really digest?

One paper I read from a study in Calgary, Alberta said that Crabapples (Malus spp.) made up about 33.88% of Coyote diets between August 2006 -September 2007. That’s a third of their diet! Since Apples persist through the Winter, it makes sense that this could be a common food source for them in Winter. Another cool thing that was noted in the paper (linked below) was that Coyotes seemed to consume less anthropogenic food items in the Winter than in any other time of year. This might be because humans spend less time outside in the Winter and that might mean less human trash strewn about for Coyotes to get a hold of. Interesting…

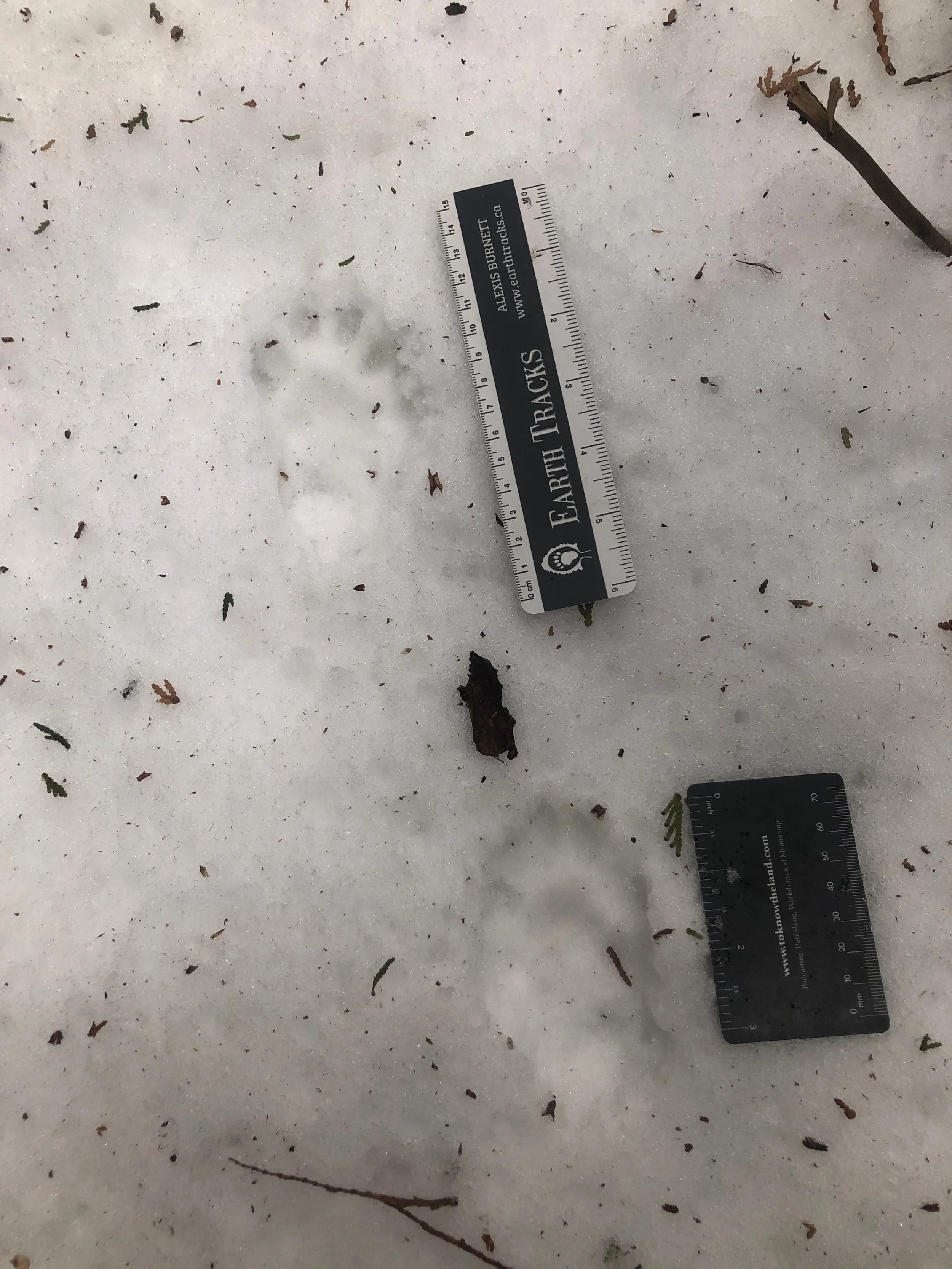

As we wandered on, we came across a fairly clear looking Fisher (Pekania pennanti) trail. It wasn’t so clear in the beginning but as we walked along and the search image of the track became more and more burned into our minds, the trail stood out like blood in the snow.

I filmed a small section of the trail and say in the recording that the tracks were 6 cm (2⅜ in) wide, and that I measured about 8.89 cm (3½ in) trail width on the 2x2 lope.

I believe it was only a moment after I stopped recording that we realized that there were actually two Fisher trails, with one trail showing larger tracks than the other trail, perhaps indicating a male and female? From memory, one of my colleagues who was there recalled the tracks of the two individuals as being 5.75 cm (2¼ in) and 7 cm (2¾ in). Perhaps in the video I was following the smaller of the two, which is kind of awesome, considering that 6 cm track width would be from the small one!

As I mentioned above, we were wondering if the two Fishers were a male and female moving together? In my research I have been looking at the amazing book “The Fisher : Life history, ecology, and behaviour” by Roger A. Powell (University of Minnesota Press, 1993), and in that book Powell cites two interesting papers attempting to see if we can tell the sex of a Fisher based on different measurements of the foot or foot pads. Here is the quote :

Trappers' accounts and early scientific reports claimed that it was possible to determine a fisher's sex by its track size. Coulter (1966) measured the hind-paws of 38 male fishers and 27 female fishers. The lengths ranged from 8.6 to 12.5 centimeters in females and from 10.0 to 13.5 centimeters in males. Johnson (1984) measured the pad dimensions of 10 male and 8 female fishers. Lengths of neither forepaw nor hindpaw foot pads differed significantly between the sexes, but widths did. The widths of forepaw pads averaged 4.8 centimeters (range 3.8-5.4) for males and 3.9 centimeters (3.8-4.1) for females; the widths of hindpaw pads averaged 4.7 centimeters (3.8-5.1) for males and 3.9 (3.5-4.5) for females. Even though the distributions of the total length of hind-paws and pad widths of fore- and hindpaws were different for the two sexes, the dimensions overlapped, except at the extremes. Thus, it is not possible to determine positively a fisher's sex from its foot dimensions or track size unless the foot length is less than 10 centimeters or greater than 12.5 centimeters (this occurs in only about 15% of fishers) or unless the width across the pads is less than 3.8 centimeters or greater than 5.4 centimeters.

I wish I had understood these ranges before hand and could have considered them in the field and tried to measure for the differences. Another means of possibly sexing Fishers in the field is noting if they have climbed any trees while you are following their trails. Here is a quote from the species profile on Fishers from “Mammal Tracks and Sign, 2nd ed” by Elbroch and McFarland (Stackpole Books, 2019).

Competent climbers, and spend time hunting in the trees as well as on the ground. However, large males spend considerably less time in trees than do the much smaller and lighter females, so much so that climbing itself is a decent indicator of the sex of the animal that made the trail you are following (Powell 1993).

We followed the Fishers along a downed Cedar which acted like a shaky bridge across the Boyne River, and up a fairly steep incline until we came across a spot on the trail where the Fishers had intersected with an Eastern Cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus), only all that remained of the Cottontail was some loose patches of fur, some snow diluted blood, and a piece of the premaxilla and some incisors.

I couldn’t tell if the Fishers had killed the Cottontail, or if they had consumed any, or interacted much at all with the Cottontail. The mortality site seemed older than the Fisher trail and there were no sign of Fisher tracks in the midst of the Cottontail remains. If I remember correctly, the Fishers skirted the site and moved on towards a large pile of fallen trunks and branches of more Eastern White Cedars. Sometimes this is called Course Wood Debris (CWD) and this is great for Fisher nesting, so I wonder if either of the Fishers will be back come birthing season come Spring?

We too headed towards the CWD and clamoured over it all and right in the center of the pile was a depressed area, still covered with snow where there was two more tufts of Cottontail fur as well as two scats, one wider and longer than the other. These looked like Fisher scat, though the larger one was larger than what I have found in the past.

When we broke up one of the scats we noticed that it had some bone fragments and coarse hairs, which may have been a little bit darker than most Cottontail hair I have seen though there may have been hair from multiple animals, but more than likely, the scat was probably filled with hair, bone and the debris of Cottontail remains. It seems that the Cottontail is a big part of the Fisher diet.

I want to jump ahead to the following day because there was an important discovery made while we were walking again along the Boyne River, heading East, along with the flow of the river.

I believe Alexis was ahead and had stopped as he had noticed something out of baseline amidst the woody debris in the snow. When I walked up I stopped and noticed it as well. Ahead of us, upside down in the snow was the skull of a White-tailed Deer. We stood silently for a few seconds taking in the scene and scanning the area. The others were catching up and as they did, I slipped off to check out a mandible which, too, was nearly covered in snow, with only the half chewed coronoid process sticking out from the blanket of white.

We decided that we should all take our time to explore this area and see if we could discover anymore remains of the deer as this looked like a spot where, likely, some Coyotes were feeding on the remains.

As everyone searched, a couple more pieces were found, including a leg, a piece of one of the scapula, and a loose thoracic vertebrae.

We decided to stop here in this spot for lunch so we could better take our time and examine the bones we found in hopes of learning a little bit more about the deer and the Coyotes who were feeding on the remains. First I believe we looked at the leg and tried to determine which leg of four it was. We determined the leg was a front leg based on the presence of the ulna and radius bones which are only found on the front legs of deer. Since we then understood that this was a front leg, we then looked at the proximal end of the metacarpal bone to examine which side was wider - the wider side being the medial side, toward the midline of the body. The wider end was on the right, implying that this was the left leg. For a detailed look into how we determined left vs right from a metacarpal bone, check out this post here.

Left front leg of a White-tailed Deer

What I was curious about when we looked at this was the shape and location of the break on the both the metacarpal bone as well as the humerus. I have seen long bones broken like this before and have heard on an online track and sign study call in the past that this is similar to how wolves break the long bones of their prey. Is this form and location of the break indicative of large canids? Can we use this as a tell-tale sign that canids have been feeding on the carcass? The fracture on the bones sort of spiral or curve around the shaft of the long bone. These are called helical or spiral fractures as they curve like a helix around the shaft. These fractures are a fairly common find when a few different carnivores consume an animal with long bones such as deer, Moose (Alces alces), or other Cervids. Many bears (Ursus spp.) and canines (Canis spp.) will leave sign like this on long bones.

Why may carnivores break these bones? The inside of the bones enclosed the bone marrow, which is full of fat, collagen, vitamins and minerals which are very helpful for any animal and gaining access would be a very worthwhile endeavour. This sign is something I will be looking for more of at mortality sites in the future.

We followed a few more interesting trails from this spot, including a pretty fresh Coyote trail, with very fresh scat, but I am feeling like this blog post has gone on beyond my own interest in writing it. Check out the books and links below if you want to learn more.

Big thanks to my tracking colleagues for this great and memorable weekend of adventure.

To learn more :

Animal Skulls by Mark Elbroch. Stackpole Books, 2006.

Vermont Mammal Atlas entry on Southern Red-backed Voles

Arboreal behaviour of the red-back vole, Clethrionomys gapperi. Animal Behaviour 16:418–424. Getz, L. L., and V. Ginsberg. 1968.

Habits of the Short-tailed Shrew, Blarina brevicauda (Say) by A. Franklin Shull. The American Naturalist, 1907.

Conspecific Killing and Cannibalism by a Free-Ranging Northern Short-Tailed Shrew (Blarina brevicauda) by Brent M. Graves & Suzanne M. Petschke. Northeastern Naturalist, 2026.

Spatial and Temporal Variation of Coyote (Canis latrans) Diet in Calgary, Alberta by Victoria M. Lukasik and Shelley M. Alexander. Cities and the Environment (CATE), 2012.

The Fisher : Life history, ecology, and behaviour by Roger A. Powell. University of Minnesota Press, 1993. (link to archive.org library copy)

Mammal Tracks and Sign, 2nd ed. by Mark Elbroch and Casey McFarland. Stackpole Books, 2019.

Metacarpal or metatarsal? blog post at toknowtheland.com